School-Based Service Delivery in Speech-Language Pathology

This resource is designed to provide information about the range of service delivery models in schools, considerations for providing these services, and relevant resources. Information included will assist speech-language pathologists (SLPs) in meeting the tenets of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; 2004) by delivering a free and appropriate public education program (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE) for students with communication disabilities in schools.

Service delivery is a dynamic process whereby changes are made to:

- Setting – the location of treatment (e.g., home, community-based, speech-language therapy room, within the school,classroom).

- Dosage – the frequency, intensity, and duration of service.

- Format – the type of session.

- Provider – the person providing the treatment (e.g. SLP, speech language pathology assistant, trained volunteer, caregiver).

According to Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), services to children from birth to age 3 should be family centered and provided in natural environments, such as the child's home and community settings, to the greatest extent appropriate to meet the individual needs of the child. For more information and resources on birth to age 3, see ASHA's Early Intervention resource.

Similar provisions are provided under Part B of IDEA for preschool and school-age students (ages 3–21 years). These provisions require that children with disabilities be provided with a FAPE and be educated in the least restrictive environment. LRE means being educated with children who do not have disabilities "to the maximum extent appropriate" to meet the specific educational needs of the student. See IDEA Part B: Individualized Education Programs and Eligibility for Services.

On this page

Approaches to Service Delivery

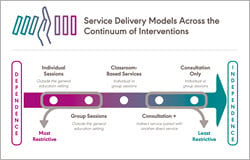

Selecting the most appropriate service delivery model is a fluid process. While no single model is appropriate for all students, one must understand the range of service delivery models as well as the advantages and limitations of each model (Nippold, 2012). Student outcomes may be improved if a flexible approach to scheduling and service delivery is adopted. The frequency, location, duration, and intensity of services should be reviewed and revised based on various factors, including:

- Student progress and changing needs throughout the school year

- Access to the general curriculum and state standards

- Promotion of skills that allow the student to improve their academic, social, and emotional functioning

- Demands of the classroom, community, and family

- Cultural considerations (see ASHA's Practice Portal page on Multilingual Service Delivery and Cultural Responsiveness)

- Team-based decision making (see ASHA's Interprofessional Education/Interprofessional Practice [IPE/IPP] resource)

Challenges in Services Delivery

ASHA school-based members have reported that some local education agencies (LEAs) place restrictions on service delivery, such as limiting speech-language services to small-group pull-out intervention only, or requiring only classroom-based services, or preventing consultative/indirect services. Restricting service delivery prevents the individualized education program (IEP) team from developing an education program that meets the individual needs of the child, as services must meet a predetermined format, rather than reflect the needs of the child. Furthermore, caseloads become inflated with children making limited or no progress due to the inappropriate delivery of services. For more information regarding varied service delivery in all settings, see Varied Service Delivery.

To help SLPs think through service delivery, ASHA created a Varied Service Delivery Worksheet [PDF]. This resource serves as a framework for determining services that are the best fit for your students in light of the many factors SLPs must consider. Varied or flexible service delivery allows the SLP to focus on individual student needs, ensure the relevance of speech-language services and reflect on treatment effectiveness. The student moves from dependence to independence in their skills. See IDEA Part B: Continuum of Service Delivery Options.

To help SLPs think through service delivery, ASHA created a Varied Service Delivery Worksheet [PDF]. This resource serves as a framework for determining services that are the best fit for your students in light of the many factors SLPs must consider. Varied or flexible service delivery allows the SLP to focus on individual student needs, ensure the relevance of speech-language services and reflect on treatment effectiveness. The student moves from dependence to independence in their skills. See IDEA Part B: Continuum of Service Delivery Options.

Making changes in service delivery may require advocacy on the part of the individual SLP or team of SLPs at the local or state level. Here are some key questions to ask yourself as you advocate to effect change in the school setting:

- How will service delivery changes benefit the students and their families?

- How will changes provide more opportunities to support the student throughout the school day by working collaboratively with other school team members as a part of interprofessional practice (IPP)? See ASHA’s How To: Advocate for IPP in Your Clinic or School

- How will changes allow for more efficient and effective services?

Research and Evidence

- Articles based on the use of various service delivery models and approaches can be found using ASHAWire. Additionally, see this special collection of articles on School Service Delivery | ASHAWire Special Collection.

- ASHA's Evidence Maps are designed to assist clinicians with making evidence-based decisions. Each Evidence Map provides information related to assessment of, treatment of, and service delivery for individuals with various communication disorders.

- ASHA’s Practice Portal resources are designed to facilitate clinical decision making by providing resources on clinical topics and linking to available evidence. Go to ASHA Practice Portal.

Settings

The school-based SLP may provide speech-language services in a variety of locations based on a student's needs, goals, performance and communication partners.

The school-based SLP may provide speech-language services in a variety of locations based on a student's needs, goals, performance and communication partners.

Speech-Language Resource Room

Services provided in a separate room—away from the general education classroom—have long been the traditional location for speech-language service delivery. This location allows for focused individual or small-group service delivery but removes students from their peers who are typically developing, and some classroom instructional time is missed.

Classroom-Based Services

By providing classroom-based speech-language services, SLPs work closely with teachers and classroom staff—along with other specialized instructional support personnel (SISP)—to collaboratively address students' goals inside the general education classroom. This increases team coordination and competency to provide assistance and support to students. When SLPs model and instruct on how to implement recommended accommodations and modifications, results include improved communication interactions within the classroom setting.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA) requires school districts to educate students with disabilities in their least restrictive environment (LRE) to the maximum extent appropriate. LRE means students with disabilities should learn with their peers without disabilities in the general education classroom as much as possible

Determining which classroom-based service delivery model to use within the general education classroom is based on student need and collaboration with the teacher. A variety of in-class models are in use (Cook & Friend, 1995):

- Supportive co-teaching—The SLP and teacher partner together as co-teachers. One takes the lead in instructing the class while the other moves among students in order to provide prompts, redirection, or direct support and vice versa.

- Complementary co-teaching—The SLP and teacher partner together as co-teachers during whole-group instruction. One enhances the instruction provided by the other co-teacher by providing visuals, examples, paraphrasing, and modeling.

- Station teaching—instructional material is divided into parts, with the SLP and the classroom teacher(s) each taking a group of students. Students rotate to each station, or learning center, for instruction.

- Parallel co-teaching—the students are divided, and the classroom teacher and the SLP each instruct a designated group of students simultaneously in different areas of the same classroom, with the SLP taking the group of students that needs more modification of content or slower pacing in order to master the educational content.

- Team co-teaching—the SLP and the classroom teacher plan, teach, and assess all of the students in the classroom. Capitalizing on the strengths and skill sets of the SLP and the teacher, these teaching partners alternate between serving as the lead or providing support.

- Supplemental teaching—one person (usually the teacher) presents the lesson in a standard format while the other person (usually the SLP) adapts the lesson.

See the Florida Inclusion Network for Collaborative Teaching videos highlighting these collaborative teaching models.

Do you need help explaining classroom-based service delivery to the families of your students? ASHA has a letter template [PDF] for you to use.

Other Educational Settings

Speech-language services may be provided in a variety of educational settings, such as the playground, media center, lunchroom, vocational training site, music classroom, physical education room, and other classrooms. IDEA mandates that services be provided in the least restrictive environment and/or most natural setting.

Telepractice

Telepractice uses telecommunications technology to deliver speech-language services remotely. Technology allows the clinician to link to the student for assessment, intervention, and/or consultation. Studies have demonstrated that telepractice can be an effective service delivery model. See ASHA's Telepractice and Telepractice evidence map.

Factors to consider in schools when using telepractice as a service delivery option include:

- Compliance with licensure and teacher certification requirements

- Appropriate client selection

- Creating an environment conducive to learning (see ASHA Facilitator Checklist for Telepractice Services in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology [PDF])

- Providing suitable equipment and appropriate technology (see ASHA Telepractice Checklist for School-Based Professionals [PDF])

- Maintaining privacy and security (see Considerations for Group Speech-Language Treatment in Telepractice)

- Meeting IDEA documentation and notification requirements (see ASHA Telepractice Documentation Data Checklist for School-Based SLPs [PDF]

- Adhering to ASHA's Code of Ethics

- Ensuring that the quality of services is comparable to that of services provided via in-person intervention

- Working simultaneously with groups of students in a hybrid model (e.g., in-person and via telepractice; see Ways to Work With Students Simultaneously Live and Online)

Dosage

Dosage

Making Dosage Determinations for Service

The school-based SLP guides a student's IEP or 504 team in making determinations regarding the frequency, intensity and duration of speech-language services.

Scheduling

Traditional Weekly Schedule

The SLP schedules students for services on the same time/day(s) every week. The location and group size can and may vary; for example, the SLP may provide one session of individual pullout treatment per week and may alternate small-group pullout sessions with classroom-based service delivery every other week.

Receding Schedule

The SLP provides direct services in intense, frequent intervention for a period of time and then reduces direct services while increasing indirect services. For example, in the first semester, the SLP works with a student 90 minutes per week on individualized education program (IEP) articulation goals. In the second semester, the SLP provides 15 minutes of direct services and 30 minutes of indirect services per week to allow for independent practice of target sounds and opportunities to monitor generalization with teacher and family (Rudebusch & Weichmann, 2013).

Cyclical Schedule

The SLP first provides direct services to students for a period of time and then follows that up with no services—or indirect services—for a period of time. The focus in the first phase is on learning new skills; the focus in the second phase is on monitoring the stabilization of skills.

The 3:1 model is an example of a cyclical schedule. Direct services are conducted for 3 weeks in a row, followed by indirect services and activities in the 4th week. IEPs reflect the service frequency (e.g., [direct service × minutes 3×/month] + [SLP consult × minutes 1×/month]). The week of indirect services could be referred to as a "student support week" to document that services are still being provided during that week.

The 3:1 model is an example of a cyclical schedule. Direct services are conducted for 3 weeks in a row, followed by indirect services and activities in the 4th week. IEPs reflect the service frequency (e.g., [direct service × minutes 3×/month] + [SLP consult × minutes 1×/month]). The week of indirect services could be referred to as a "student support week" to document that services are still being provided during that week.

Sharing informational handouts and letters [DOC] with parents and staff can be particularly helpful. Doing so highlights the benefits of the 3:1 schedule and informs them of the scheduled student support weeks (indirect) for the school year. Christina Bradburn shares ideas about how to talk with families and staff about implementing a 3:1 model in this video, Maximize Your Impact With the 3:1 Service Delivery Model - ASHA Stream.

Block Schedule

Speech-language sessions are longer but less frequent, often reflecting a middle school's or high school's master block schedule, where there are fewer but longer classes every day or every semester. This schedule allows for fewer interruptions to the student's school day. Because class periods are longer, the SLP can provide a pullout session to practice a skill—immediately followed by in-class services to generalize the skills—all within the same class period (Rudebusch & Wiechmann, 2013).

Blast or Burst Schedule

In this schedule, speech-language services are provided in short, intense bursts (i.e., 15 minutes 3 times per week). This model allows the SLP to provide (a) individualized services, with less travel time to and from the therapy room as services could be provided right outside the classroom, and (b) less out-of-class time (Kuhn, 2006; Rehfeld & Sulak, 2021).

Group Size

Group sizes vary and fluctuate over time in response to dynamic service delivery. Considerations in grouping students includes grade level, abilities, similarities or compatibility of IEP goals. Student placement should be based on individual needs, where the most progress and benefit will occur. ASHA does not have a practice policy on determining group size in school based intervention. However, some states provide guidance based on third party payer mandates.

Indirect or Consultative Services

When providing indirect or consultative services, the SLP works with the student's teachers, staff, and family. Activities include the following:

- Analyzing, adapting, modifying, or creating instructional materials

- Programming or instructing others on augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices

- Participating in team or IEP meetings

- Monitoring student progress via data checks and observations

- Conducting assessments or gathering baseline data

- Planning interventions

- Collaborating with teachers, other SISP, and families

Provider and Practicing at the Top of the License

Practicing at the top of the license has implications for SLPs in school settings. Many schools are experiencing tight budgets, large caseloads, and shortages of qualified providers; therefore, it is important that SLPs in school settings focus on providing professional services that (a) require the skills of an ASHA-certified SLP and (b) are within the Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology. Routine tasks may be performed by other professionals (e.g., speech-language pathology assistants [SLPAs], paraprofessionals, etc.) under the supervision of the SLP or in concert with other SISP on the school team.

Workload

Workload refers to all activities required and performed by school-based SLPs and other professionals. Caseload (or the number of students served) is just one part of the SLP's workload. Reasonable workloads allow for optimal service delivery to students to meet their individual needs as required under IDEA. The workload analysis approach is explained in ASHA's Caseload and Workload Practice Portal resource.

IEP Documentation

IEP documentation can influence the service delivery model that an SLP uses to provide services in schools. According to ASHA's Practice Portal Page on Documentation in Schools, services must be provided "according to what is agreed upon and documented in the IEP, including the frequency, type, duration, and location of services." Service considerations must be individualized according to IDEA. Caseloads that have a large percentage of students receiving the same amount and frequency of services (e.g., 2×/week for 30 minutes) may not be appropriately meeting the IDEA service provision requirements.

Some districts or states are more flexible in how services can be documented on the IEP. They allow "minutes per reporting period or semester" as acceptable means of recording frequency and duration of services. Documentation that allows for contact hours or services per month would allow SLPs to vary service provision while still providing appropriate services that meet the student's needs in accordance with IDEA. IEPs could also reflect changes in the frequency and location of services, depending on the individual student's needs and progress (e.g., start with more intensive services to teach a new skill and transition to less frequent or in-class services). Check with your state Department of Education or district regarding their policies for reporting services.

ASHA's professional issues statement titled Roles and Responsibilities of Speech-Language Pathologists in Schools suggests a framework for providing services in schools. Included in this professional issues statement is a list of the SLP's range of responsibilities; several of those responsibilities relate to service delivery:

- Program design—It is essential that SLPs configure school-wide programs that employ a continuum of service delivery models in the least restrictive environment for students with disabilities and that they provide services to other students as appropriate.

- Collaboration—It is important that collaboration occur with parents/guardians and other support personnel (currently referred to as SISP) to provide appropriate services.

- Leadership—It is important to advocate for appropriate services and ensure that service delivery is meeting the intent of IDEA.

Code of Ethics

ASHA's Code of Ethics (2023) is a framework of principles and standards of practice for providing speech-language pathology and audiology services. Ethical practice is required for maintaining both the ASHA Certificate of Clinical Competence (CCC) and the state license, as well as most educational certifications. SLPs need to adhere to ASHA's Code of Ethics when making decisions regarding service delivery in schools. The most recent Code of Ethics, revised in 2023, devotes particular attention to interprofessional practice. Rule A of Principle IV states, "Individuals shall work collaboratively, when appropriate, with members of one's own profession and/or members of other professions to deliver the highest quality of care." Additional information on ethical issues in schools can be found on ASHA's webpage titled Ethics and Schools Practice.

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2023). Code of ethics. Rockville, MD: Author. Retrieved from www.asha.org.

Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995). Co-teaching: Guidelines for creating effective practices. Focus on Exceptional Children, 28(3), 1–16.

Crutchley, S., Dudley, W., & Campbell, M. (2010). Articulation assessment through videoconferencing: A pilot study. Communications of Global Information Technology, 2, 12–23.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act. (2004). Public Law 108-446, 20 U.S.C. 1400 et seq.

Kuhn, D. (2006). SPEEDY SPEECH: Efficient service delivery for articulation errors. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 11(1), 3–7. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1044/sbi7.4.11.

Nippold, M.(2012). Different service delivery models for different communication disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43, 117–120. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2012/ed-02).

Rehfeld, D.M. & Sulak, T.N. (2021) Service delivery schedule effects on speech sound production outcomes. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52, 728-737. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_LSHSS-20-00068.

Rudebusch, J., & Wiechmann, J. (2013, August 01). Time block after time block. The ASHA Leader, 18(8), 40–45.