Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing

The scope of this page is feeding and swallowing disorders in infants, preschool children, and school-age children up to 21 years of age. This page covers pediatric dysphagia and pediatric feeding disorder (PFD). These are separate diagnoses but may co-occur.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are the preferred providers of dysphagia services and are integral members of an interprofessional team. Interprofessional collaboration is the preferred practice pattern.

See the Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Evidence Map for summaries of the available research on this topic.

Feeding and Swallowing

Feeding is the term for supplying someone with nourishment. The term feeding includes all aspects of eating or drinking, including gathering and preparing food and liquid for intake, sucking or chewing, and swallowing (Arvedson & Brodsky, 2002). Feeding may also be achieved by non-oral routes (e.g., percutaneous endoscopy gastronomy tube). Feeding provides children and caregivers with opportunities for communication and social experiences that form the basis for future interactions (Lefton-Greif, 2008).

Swallowing is a complex skill during which saliva, liquids, and foods are transported from the mouth into the stomach while keeping the airway protected. The integration of six cranial nerves and over 30 muscles responsible for swallowing ensures the precise coordination required to safely and effectively transport foods and liquids (Steele & Miller, 2010). Swallowing is commonly divided into the following four phases (Arvedson & Brodsky, 2002; Logemann, 1998):

- Oral preparatory—This is a voluntary phase during which foods or liquids are manipulated in the mouth to form a cohesive bolus, which includes sucking liquids, manipulating soft boluses, and chewing solid foods.

- Oral transit—This is a voluntary phase that begins with the posterior propulsion of the bolus by the tongue and ends with the initiation of the pharyngeal swallow.

- Pharyngeal—This phase begins with a voluntary pharyngeal swallow that, in turn, propels the bolus through the pharynx via an involuntary contraction of the pharyngeal constrictor muscles.

- Esophageal—This is an involuntary phase during which the bolus is carried to the stomach through the process of esophageal peristalsis.

Feeding Disorders

The term feeding disorders describes a range of eating activities and behaviors that may or may not include problems with swallowing. Goday, et. al (2019) note the following:

- Pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) is any difficulty a person has with oral intake as compared to same age peers. PFD is associated with medical, nutritional, feeding skill, and/or psychosocial dysfunction. Impaired oral intake is the inability to consume sufficient foods and liquids to meet nutritional and hydration requirements.

- PFD should be diagnosed only if not better attributed to body image disturbances or dysmorphia.

- Impairments result in activity limitations or participation restrictions due to interactions with personal and environmental factors.

- PFD may be diagnosed as acute if the disorder has been present for less than 3 months or chronic if the disorder has been present for 3 months or more.

Food avoidance (e.g., throwing food on the ground, refusing to take a bite) should be interpreted as communicating a message—not as conveying a negative behavior. This approach can lead to better collaboration between the child and the adult (e.g., caregiver, clinician).

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text rev.; American Psychiatric Association, 2022), avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)[1] is an eating or a feeding disturbance (e.g., apparent lack of interest in eating or food; avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food, concern about aversive consequences of eating) associated with one (or more) of the following:

- significant weight loss (or failure to achieve expected weight gain or faltering growth in children)

- significant nutritional deficiency

- dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements

- marked interference with psychosocial functioning

Selective eating in ARFID is due to disinterest in eating or food in general, sensory sensitivity, and/or a fear of consequences (e.g., choking; Kambanis et al., 2020).

SLPs may screen or make referrals for ARFID but do not diagnose it or treat it—ARFID is a mental health disorder. ARFID and PFD are different disorders, but they may co-occur. ARFID differs from PFD in the following ways:

- ARFID does not include children whose primary challenge is a skill deficit (e.g., dysphagia).

- ARFID includes a severity of eating difficulty that exceeds the severity typically associated with a certain condition (e.g., Down syndrome).

[1] An Important Note About ARFID: Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is considered a mental health disorder and outside the scope of practice of an SLP. Although SLPs may screen or make referrals for ARFID, they do not diagnose or treat it. The information about ARFID in this section is meant to be an informational resource for SLPs—although they do not diagnose or treat ARFID, they still need to know about it in the context of clinical patient care.

Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia)

Dysphagia is a swallowing disorder involving difficulty processing and/or moving liquid and/or food boluses through the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, or gastroesophageal junction. SLPs also recognize causes and signs/symptoms of esophageal dysphagia and make appropriate referrals for its diagnosis and management.

The consequences and associated symptoms of feeding and swallowing disorders may include

- aspiration pneumonia and/or compromised pulmonary status;

- dehydration;

- feeding and swallowing problems that persist into adulthood;

- food aversion;

- gastrointestinal issues (e.g., motility disorders, constipation, diarrhea);

- ongoing need for enteral (gastrointestinal) or parenteral (intravenous) nutrition;

- oral aversion;

- poor weight gain and/or undernutrition;

- psychosocial effects on the child and their family; and

- undernutrition or malnutrition.

Incidence refers to the number of new cases identified in a specified time period.

Prevalence refers to the number of children who are living with feeding and swallowing problems in a given time period.

It is assumed that the incidence of feeding and swallowing disorders is increasing because of the improved survival rates of children with complex and medically fragile conditions (Lefton-Greif, 2008; Lefton-Greif et al., 2006; Newman et al., 2001) and the improved longevity of persons with dysphagia that develops during childhood (Lefton-Greif et al., 2017).

Estimated reports of the incidence and prevalence of pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders vary widely due to factors including

- variations in the conditions and populations sampled;

- how the terms pediatric feeding disorder, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID; please see the “ARFID” section above for further details), and/or swallowing impairment are defined; and the choice of assessment methods and measures (Arvedson, 2008; Lefton-Greif, 2008). The data below reflect this variability.

According to the 2022 National Survey of Children’s Health (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2022), survey interviews indicated that within the past 12 months, 1.6% of children (approximately 1,188,828) ages 0–17 years were reported to have eating or swallowing problems because of a health condition. Prevalence varied for a variety of co-occurring conditions:

- Cerebral palsy (ages 0–18 years)—The prevalence of swallowing problems was 50.4%. There was a trend toward increased swallowing difficulty with more severely impaired functioning, but this did not reach the level of significance (Speyer et al., 2019).

- Craniofacial microsomia—The prevalence of swallowing difficulties was estimated to be 13.5% (van de Lande et al., 2018).

- Laryngeal cleft, type 1—The prevalence of swallowing difficulties was 86%, which decreased by up to 26% postsurgical intervention (Liao & Ulualp, 2022).

- Laryngomalacia—The prevalence of swallowing disorders was 72%, which was reduced by 59% postsurgery (Rossoni et al., 2024).

- Unilateral vocal fold paralysis (partial or complete)—The prevalence of dysphagia was 92.9%, while 53.6% exhibited silent aspiration (Irace et al., 2019).

- Congenital heart disease—The overall pooled prevalence of dysphagia was 42.9%, with the pooled mean prevalence of aspiration in this population estimated to be 32.9% (Norman et al., 2022).

- Neuromuscular diseases (ages 2–18 years)—The prevalence of dysphagia was 47.2% (Kooi-van Es et al., 2020).

- Acute stroke

- Newborns—The frequency of feeding and swallowing impairment was 39%. At the time of discharge, feeding and swallowing disorders persisted for 19% of newborns (Sherman et al., 2021).

- Children—The frequency of feeding and swallowing impairment was 41%. At the time of discharge, feeding and swallowing disorders persisted for 17% of children (Sherman et al., 2021).

The overall annual prevalence of pediatric feeding disorders in the United States is estimated to be between 2.7% and 4.4% (Kovacic et al., 2021). Estimates varied across a variety of co-occurring conditions:

- Preterm

- Infants (ages 6–12 months) who were born preterm—The prevalence of feeding problems was 43%.

- Children (ages 1–7 years) who were born preterm—The prevalence of feeding problems was 25% (Walton et al., 2022).

- Cerebral palsy (ages 0–18 years)—The prevalence of feeding problems was 53.5%. There was a trend toward increased feeding difficulty with more severely impaired functioning, but this did not reach the level of significance (Speyer et al., 2019).

- Craniofacial microsomia—The prevalence of feeding difficulties is estimated to be 26.4% (Caron et al., 2018).

- Cleft palate

- With Pierre Robin sequence—The prevalence of feeding difficulties was estimated to be 91%.

- With isolated cleft palate only—The prevalence of feeding difficulties was estimated to be 72% (Paes et al., 2017).

- Acute stroke

- Newborns—The frequency of feeding and swallowing impairment was 39%. At the time of discharge, feeding and swallowing disorders persisted for 19% of newborns (Sherman et al., 2021).

- Children—The frequency of feeding and swallowing impairment was 41%. At the time of discharge, feeding and swallowing disorders persisted for 17% of children (Sherman et al., 2021).

- Autism—The prevalence of food selectivity was 69.1% in children and adolescents, with 48.8% displaying food selectivity several times per week or even daily. The prevalence of mealtime behaviors was 64.3% (Babinska et al., 2020).

Pediatric feeding disorder (PFD) may co-occur with dysphagia. Signs and symptoms of PFD vary based on the domain(s) affected and the child’s age and developmental level. They include, but are not limited to, the following (Goday et al., 2019):

Medical Factors

- Slowed motility, vomiting, and/or constipation due to gastrointestinal (GI) conditions

- Nasopharyngeal and laryngeal perceptual changes, such as stertor (noisy breathing, low-pitched sound that sounds like snoring), stridor (noisy breathing, high-pitched sound on inspiration), and congestion during or after eating

- Frequent respiratory illnesses, tachypnea (fast breathing), or apnea (temporary cessation of breathing)

- Cyanosis (turning blue), tachycardia (fast heart rate), bradycardia (slowed heart rate), and mottling (blotchy, red and purple marbling on the skin) due to cardiac conditions

- Neurological impairments characterized by severe motor and cognitive delays

Nutritional Factors

- Malnutrition

- Restricted dietary diversity or quality, quantity, and/or variety of beverages and foods consumed

- Micronutrient deficiencies related to the exclusion of certain food groups

Feeding Skill Factors

- Oral sensory impairments, including

- limited tolerance for age-appropriate textures and viscosities, which may be associated with specific flavors, temperatures, tastes, bolus size, or appearance;

- lack of awareness of food within the mouth, poor bolus formation, anterior loss, large bolus sizes, and gagging or refusal of liquid and food textures that provide inadequate sensory input; and

- gagging with specific textures or bolus sizes, the need for excessive chewing, and limited variety of intake resulting in the need for bland flavors, finely grained textures, small bolus sizes, and room-temperature foods.

- Oral motor impairments, including

- poor bolus control and manipulation resulting in anterior loss or gagging and coughing;

- inefficient intake;

- slow, ineffective mastication;

- oral residue;

- poor secretion management; and

- an uncoordinated suck–swallow–breathe sequence.

- Pharyngeal swallowing impairments, including

- audible or gulping swallows;

- wet vocalizations;

- multiple swallows per bolus;

- throat clearing or coughing; and

- chronic congestion.

Psychosocial Factors

- Learned feeding aversions

- Stress and distress during mealtimes

- Disruptive behavior during mealtimes

- Food overselectivity or picky eating

- Failure to advance to age-appropriate diet

- Grazing

- Caregiver use of maladaptive strategies to increase intake

Oral feeding requires coordination of the central and peripheral nervous systems, the oropharyngeal mechanism, the cardiopulmonary system, and the GI tract, with support from craniofacial structures and the musculoskeletal system. Because of how these systems interact, an impairment in one area can lead to a disruption or dysfunction in another, resulting in PFD (Goday et al., 2019). PFD may be caused by any singular factor or a combination of factors across the four domains:

Medical Factors

- GI tract conditions, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, eosinophilic esophagitis, or motility disorders

- Oropharyngeal and laryngeal anomalies, such as laryngomalacia, vocal fold paralysis, or laryngeal cleft

- Pulmonary or other aerodigestive conditions, such as chronic lung disease

- Congenital heart disease or other cardiac conditions

- Neurological impairments, such as cerebral palsy

Nutritional Factors

- Metabolic disorders

- Medication side effects resulting in decreased appetite

- Neurodevelopmental disorders that affect energy expenditure and growth

Feeding Skill Factors

- Oral sensory impairments that may lead to

- Oral hyposensitivity (or under-responsiveness)

- Oral hypersensitivity (or over-responsiveness)

- Oral motor impairments affecting lip closure, tongue movement, and chewing abilities

- Pharyngeal swallowing impairments affecting airway protection and closure and that require an instrumental evaluation to fully assess anatomy and physiology

Psychosocial Factors

The factors within the child, the caregiver, and the feeding environment that can adversely affect feeding development and ultimately contribute to and maintain PFD, such as developmental delays, mood disorders, anxiety, stress, a distracting mealtime environment, and inappropriate social influences

SLPs play a central role in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of infants and children with swallowing and feeding disorders. The professional roles and activities in speech-language pathology include clinical/educational services (diagnosis, assessment, planning, and treatment); prevention and advocacy; and education, administration, and research. See ASHA’s Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology (ASHA, 2016).

Appropriate roles for SLPs include the following:

Assessment

- Conducting a comprehensive assessment, including clinical and instrumental evaluations as appropriate

- Considering culture as it pertains to food choices/habits, perception of disabilities, and beliefs about intervention (Davis-McFarland, 2008; Villaluna & Dolby, 2024)

- Diagnosing pediatric oral and pharyngeal swallowing disorders (dysphagia)

- Recognizing signs of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and making appropriate referrals with collaborative treatment as needed

- Recommending a feeding and swallowing plan for the individualized family service plan, individualized health plan, individualized education program, or 504 plan

- Referring the patient to other professionals as needed to rule out other conditions, determine etiology, and facilitate patient access to comprehensive services

Counseling and Education

- Educating caregivers of children at risk for pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders

- Educating other professionals on the needs of children with feeding and swallowing disorders and the role of SLPs in diagnosis and management

- Educating children and their families to prevent complications related to feeding and swallowing disorders

Treatment

- Advocating for people with feeding and swallowing disorders at the local, state, and national levels

- Consulting and collaborating with other professionals, family members, caregivers, and others to develop programs

- Providing supervision, evaluation, and/or expert testimony, as appropriate

- Helping to advance the knowledge base related to the nature and treatment of these disorders

- Remaining informed of feeding and swallowing disorders research

- Serving as an integral member of an interdisciplinary feeding and swallowing team

- Providing evidence-based treatment for the remediation of pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders

SLPs who serve a pediatric population should be educated and appropriately trained to do so (ASHA, 2023). SLPs require specific knowledge of pediatric swallowing anatomy and physiology to treat pediatric feeding disorders and dysphagia.

Feeding and Swallowing Teams

Evaluation, assessment, and treatment of pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders may require the efforts of multiple specialists on an interprofessional team. Members of the feeding and swallowing team may vary across settings.

SLPs may be the team coordinator, who leads the team in

- identifying core team members and support services,

- training team members,

- facilitating communication between team members,

- tracking and documenting team activity,

- actively consulting with team members, and

- assisting in discharge planning.

School Setting Considerations

School-based SLPs play a significant role in the management of feeding and swallowing disorders. SLPs assess and treat students and educate families, teachers, and other professionals who work with the student. SLPs develop and lead the school-based feeding and swallowing team.

Feeding, swallowing, and dysphagia are not specifically mentioned in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEA, 2004). However, school districts have a responsibility to protect the health and safety of students with disabilities, including those with feeding and swallowing disorders. Students with disabilities have the right to access services to address safe mealtimes regardless of their special education classification (IDEA, 2004).

The U.S. Department of Education acknowledges that chronic health conditions could make a student eligible for special education and related services under the disability category “Other Health Impairment,” if the disorder interferes with the student’s strength, vitality, or alertness and limits the student’s ability to access the educational curriculum.

Students who do not qualify for IDEA services and have swallowing and feeding disorders may receive services through the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504, so long as the swallowing and feeding disorder substantially limits one or more of life’s major activities.

School districts that participate in the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service Program in the schools (i.e., the National School Lunch Program) must follow regulations (see 7 C.F.R. § 210.10[m][1]) to provide substitutions or modifications in meals for children who are considered disabled and whose disabilities restrict their diet (Meal Requirements for Lunches and Requirements for Afterschool Snacks, 2021). [2]

For more information, see also Accommodating Children With Disabilities in the School Meal Programs: Guidance for School Food Service Professionals [PDF] (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2017).

[2] Here, we cite the most current, updated version of 7 C.F.R. § 210.10 (from 2021), in which the section letters and numbers are “210.10(m)(1).” The original version was codified in 2011 and has had many updates since. Those section letters and numbers from 2011 are “210.10(g)(1)” and can be found at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2011-title7-vol4/pdf/CFR-2011-title7-vol4-sec210-10.pdf

Educational Relevance

IDEA ensures free and appropriate public education and protects the rights of students with disabilities. Feeding and swallowing disorders may be considered educationally relevant and part of the school system’s responsibility to ensure

- adequate time to eat meals, which includes the ability to eat within the school’s mealtime schedule and the need for accommodations such as extended mealtime or shorter, more frequent meals;

- safety while eating and drinking at school, including access to appropriate personnel, foods, liquids, and procedures to minimize risks of choking and aspiration while eating;

- adequate nourishment and hydration so that students can attend to and fully access the school curriculum;

- student health and well-being (e.g., free from aspiration pneumonia or other illnesses related to malnutrition or dehydration) to maximize their attendance and academic ability/achievement at school; and

- skill development for eating and drinking efficiently during meals and snack times so that students can complete these activities with their peers safely and in a timely manner.

Please see the Clinical Evaluation: School Setting section below for further details.

See the Assessment section of the Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective. See Person-Centered Focus on Function: Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing [PDF] for examples of assessment data consistent with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework (World Health Organization, 2001).

Assessment and treatment of swallowing and swallowing disorders require the use of appropriate personal protective equipment and universal precautions as needed.

Clinicians may consider the following factors when assessing feeding and swallowing disorders in the pediatric population:

- Congenital abnormalities and/or chronic conditions can affect feeding and swallowing function.

- Feeding skills of premature infants will be consistent with neurodevelopmental level rather than chronological age or adjusted age.

- Positioning limitations and abilities (e.g., children who use a wheelchair) may affect intake and respiration.

- Infants cannot describe their symptoms, and children with reduced communication skills may not be able to adequately do so either. Clinicians may rely on

- a thorough case history;

- caregiver interviews;

- weight gain and growth trajectory;

- data from monitoring devices (e.g., for patients in the hospital or on home respiratory support);

- nonverbal forms of communication (e.g., behavioral cues signaling feeding or swallowing problems); and

- observations of the caregiver’s behaviors and ability to read the child’s cues as they feed the child.

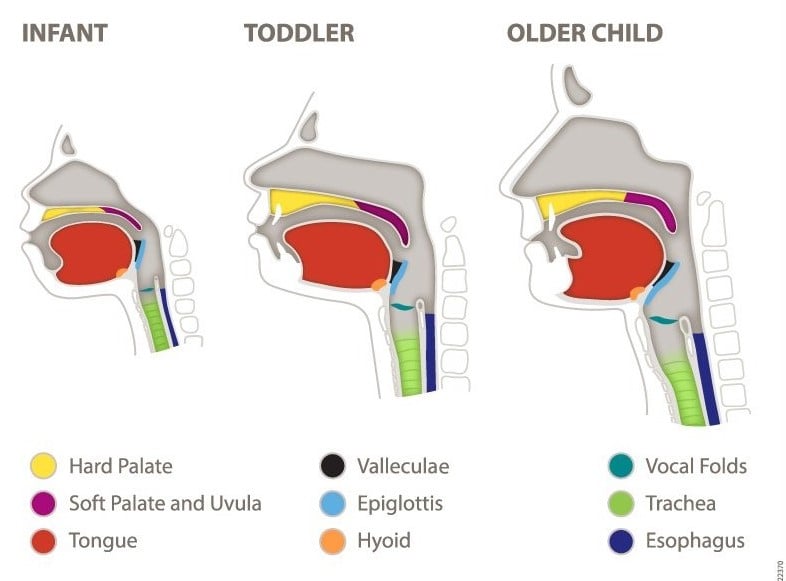

As infants and children grow and develop, the absolute and relative size and shape of oral and pharyngeal structures change. See figures below.

Anatomical and physiological differences in infants include the following:

- The tongue fills the oral cavity, and the velum hangs lower than the adult velum. The hyoid bone and the larynx are positioned higher than in adults, and the larynx elevates less than in adults during the pharyngeal phase of the swallow.

- Each swallow of solids is discrete once the infant begins eating pureed food, as opposed to sequential swallows in bottle-fed or breastfed/chestfed infants.

- Swallowing anatomy and physiology change as the child gets older (Logemann, 1998).

- The intraoral space increases as the mandible grows down and forward.

- Deciduous teeth erupt, and the buccal fat pads are reabsorbed.

- The oral cavity elongates in the vertical dimension.

- The pharynx becomes elongated and enlarged as the child grows. This happens because the space between the tongue and the palate increases, and that between the larynx and the hyoid bone lowers.

Chewing matures as the child develops (see, e.g., Delaney et al., 2021; Gisel, 1988; Le Révérend et al., 2014; Wilson & Green, 2009). Concurrent medical issues may affect this timeline. Foods given during the assessment should be consistent with the child’s current level of chewing skills.

Clinical Evaluation

A clinical evaluation of feeding and swallowing is necessary to determine the presence or absence of a feeding and/or swallowing disorder.

The evaluation may address

- eating,

- drinking,

- secretion management,

- oral hygiene,

- sensory status,

- the ability to accept food,

- the amount of diversity in their diet,

- management of oral medications,

- the caregiver’s behaviors while feeding their child, and

- the psychosocial impact of feeding and swallowing difficulties on the family-and-child dynamic.

SLPs conduct assessments in a culturally responsive manner to acknowledge and honor the family’s cultural background, religious beliefs, dietary beliefs/practices/habits, history of disordered eating behaviors, and preferences for medical intervention. Families are encouraged to bring foods and drinks common to their household and utensils typically used by the child. Typical feeding practices and positioning should be used during assessment. Cultural, religious, and individual beliefs about food and eating practices may affect an individual’s comfort level or willingness to participate in the assessment. Some eating habits that appear to be a sign or symptom of a feeding disorder (e.g., avoiding certain foods or refusing to eat in front of others) may, in fact, be related to cultural differences in meal habits or may be symptoms of an eating disorder (National Eating Disorders Association, n.d.).

SLPs do not diagnose or treat eating disorders such as bulimia, anorexia, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; in cases where these disorders are suspected, the SLP should refer to the appropriate behavioral health professional.

The clinical evaluation typically begins with a case history based on a comprehensive review of medical/clinical records and interviews with the family and health care professionals.

During a clinical evaluation, the SLP may assess the following:

- Overall physical, social, behavioral, and communicative development

- Gross and fine motor development

- Cranial nerve function

- Structures of the face, jaw, lips, tongue, hard and soft palate, oral pharynx, and oral mucosa

- Functional use of muscles and structures used in swallowing, including

- symmetry,

- sensation,

- strength,

- tone,

- range and rate of motion, and

- coordination of movement

- Head–neck control, posture, oral and pharyngeal reflexes, and involuntary movements and responses in the context of the child’s developmental level

- Observation of the child eating or being fed by a family member, caregiver, or classroom staff member using foods from the home and oral abilities (e.g., lip closure) related to

- typically used utensils or

- utensils that the child may reject or find challenging

- Functional swallowing ability, including, but not limited to, typical developmental skills and task components, such as

- suckling and sucking in infants,

- mastication in older children,

- oral containment (i.e., of bolus and secretions),

- manipulation and transfer of the bolus, and

- the ability to eat efficiently or within the time allotted at school

- Environmental factors, such as

- mealtime schedule and routine;

- distractions such as televisions and electronic devices; and

- seating, positioning, and other environmental factors that impact feeding safety and efficiency

- Psychosocial factors, including

- child and caregiver stress and other mental health factors that can affect mealtime interactions,

- caregiver approaches to feeding,

- caregiver expectations,

- caregiver–child interactions and interpretation of hunger and satiety cues, and

- the impact of feeding and swallowing needs on social interactions with adults and peers

- Ability to remain alert during intake to maintain swallow safety

- Impression of airway adequacy and coordination of respiration and swallowing

- Developmentally appropriate secretion management, which might include frequency and adequacy of spontaneous dry swallowing and the ability to swallow voluntarily

- Modifications in bolus delivery and/or use of rehabilitative/habilitative or compensatory techniques on the swallow and their effectiveness/impact

- Interventions by and referrals to

- medical or surgical specialists,

- a registered dietitian,

- a psychologist or social worker,

- an occupational therapist (OT), or

- a physical therapist (PT)

Please see the Pediatric Clinical Swallowing Evaluation Template [PDF].

Team Approach

A team approach is necessary for appropriately diagnosing and managing pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders. The severity and complexity of these disorders vary widely in this population (McComish et al., 2016).

SLPs who specialize in feeding and swallowing disorders typically lead the professional care team in the clinical or educational setting.

Additional team members may include

- family/caregivers;

- a registered dietitian;

- a lactation consultant (infants);

- a nurse;

- an OT or a PT;

- a physician, such as

- a pediatrician,

- a neonatologist,

- an otolaryngologist,

- a gastroenterologist,

- a dentist, or

- a psychologist or psychiatrist;

- a psychologist/mental health professional (outpatient or school-based);

- a social worker (outpatient or school-based);

- a classroom teacher and/or a classroom teaching assistant; and/or

- school-based administrators/leaders.

Additional medical and rehabilitation specialists may be included, depending on the type of facility, the professional expertise needed, and the specific population being served.

See ASHA’s resources on interprofessional education/interprofessional practice (IPE/IPP) and focusing care on individuals and their care partners.

For further information on the importance of a team approach, see Gosa et al. (2020), Desai et al. (2022), Homer (2008), and Dawson et al. (2024).

Screening

Screening identifies the need for further assessment and may be completed prior to a comprehensive evaluation. Swallowing screening is a procedure to identify individuals who require a comprehensive assessment of feeding and swallowing function or a referral for other professional and/or medical services (ASHA, 2004). Screening for pediatric feeding disorder and/or dysphagia may be conducted by an SLP or any other member of the patient’s care team. Individuals of all ages are screened as needed, requested, or mandated or when presenting medical conditions (e.g., neurological or structural deficits) suggest that they are at risk for pediatric feeding disorder and/or dysphagia. The purpose of the screening is to determine the likelihood that pediatric feeding disorder and/or dysphagia exists and the need for further assessment (see ASHA’s resource on swallowing screening).

Screening may include the following:

- Administration of an interview or a questionnaire that addresses the patient’s/caregiver’s perception of and/or concern with swallowing function (e.g., the Feeding Impact Scales or Family Management of Feeding).

- Monitoring the presence of the signs and symptoms of oropharyngeal and/or esophageal swallowing dysfunction.

- Patient/caregiver report or observation of difficulty with per os.

- Administration of standardized screening protocols. Please see About the Feeding Assessment Tools—Infant Feeding Care for evidence-based screening tools.

- Observation of the student while eating snacks or a meal.

- Teacher/parent interview.

All screening procedures include communication of results and recommendations to the team responsible for the individual’s care and to the patient and caregivers.

Screening may result in

- recommendations for rescreening;

- recommendations for additional assessment to determine whether, and the degree to which, feeding skill may be impaired; and

- referrals for other examinations or services (ASHA, 2004).

The medical team may make temporary recommendations (e.g., no oral intake, stipulation of specific dietary precautions) while the patient is awaiting further assessment.

Clinical Evaluation: Infants

The clinical evaluation for infants from birth to 1 year of age includes an evaluation of prefeeding skills, an assessment of readiness for oral feeding, an evaluation of breastfeeding/chestfeeding and bottle-feeding ability, and observations of caregivers feeding the child.

SLPs should have extensive knowledge of

- embryology,

- prenatal and perinatal development,

- medical issues common to preterm and medically fragile newborns,

- typical early infant development,

- neuroprotection,

- neonatal care and its influence on neurodevelopment,

- respiratory support in the hospital and at home,

- alternative feeding modalities, and

- medical comorbidities common in the neonatal intensive care unit and after discharge.

Appropriate referrals to medical professionals should be made when anatomical or physiological abnormalities are found during the clinical evaluation. The clinical evaluation of infants typically involves the following:

- A case history, which includes (Arvedson, 2008)

- gestational and birth history (to include Apgar scores if available);

- general health;

- medical comorbidities;

- pertinent medical history including growth patterns, neurodevelopmental status, orofacial structures, and cardiopulmonary and gastrointestinal function;

- any known allergies or intolerances;

- the caregivers’/family’s cultural/religious beliefs/preferences regarding food and feeding practices; and

- the caregivers’/family’s perceptions of the mealtime process related to schedule, location, specific strategies, and oral and enteral intake

- A physical examination, which includes (Arvedson, 2008)

- oral reflexes/oral peripheral examination;

- infant and caregiver interactions;

- developmental motor assessment looking at head, neck, and trunk positioning;

- respiratory status and supports;

- overall state, alertness, and autonomic functions such as temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation (physiologic stability);

- response to sensory stimulation; and

- self-regulatory behaviors

- A determination of oral feeding readiness

- An assessment of the infant’s ability to engage in non-nutritive sucking (NNS)

- Developmentally appropriate clinical assessments of feeding and swallowing behavior (nutritive sucking [NS])

- An identification of additional disorders that may have an impact on feeding and swallowing

- A determination of the optimal feeding method

- An assessment of the duration of mealtime experience, including the potential impact on physiologic stability (SLP may refer to the medical team, as necessary)

- An assessment of issues related to fatigue and volume limitations

- An assessment of the effectiveness of parent/caregiver and infant interactions for feeding and communication

- Consideration of the infant’s ability to obtain sufficient nutrition/hydration across settings (e.g., hospital, home, day care)

For further information on case history and physical examination, please see Gosa and Dodrill (2023) and Delaney (2019).

Non-Nutritive Sucking (NNS)

NNS is sucking for comfort without fluid release (e.g., with a pacifier, finger, or recently emptied breast). NNS does not determine readiness to orally feed, but it is helpful for assessment. NNS patterns can typically be evaluated with skilled observation and without the use of instrumental assessment.

A noninstrumental assessment of NNS includes an evaluation of the following:

- The infant’s oral structures and functions, including palatal integrity, jaw movement, and tongue movements for cupping and compression (Note: Lip closure is not required for infant feeding because the tongue typically seals the anterior opening of the oral cavity.)

- The infant’s ability to turn the head and open the mouth (rooting) when stimulated on the lips or cheeks and to accept a pacifier into the mouth

- The presence and strength of compression (positive pressure of the jaw and tongue on the pacifier)

- The presence and strength of suction (negative pressure created with tongue cupping and jaw movement)

- The infant’s ability to maintain stable status (e.g., oxygen saturation, heart rate, respiratory rate) during NNS

Nutritive Sucking (NS)

The clinician can determine the appropriateness of NS following an NNS assessment. Any change in physiologic, motoric, or behavioral status from baseline should be taken into consideration at the time of the assessment.

NS skills are assessed during breastfeeding/chestfeeding and bottle-feeding if both modes are going to be used. SLPs should be sensitive to family values, beliefs, and access regarding bottle-feeding and breastfeeding/chestfeeding and should consult with parents and collaborate with nurses, lactation consultants, and other medical professionals to help identify parent preferences.

Assessment of NS includes an evaluation of the following:

- sucking–swallowing–breathing coordination

- the feeding relationship—interaction between the infant and the feeder

- efficiency—volume of intake per minute

- endurance—ability to remain engaged in the feeding to finish the required volumes while sustaining appropriate feeding patterns

The infant’s communication behaviors during feeding can be used to guide a flexible assessment. These cues can communicate the infant’s ability to tolerate bolus size, if any additional postural support is needed and if swallowing and breathing are no longer synchronized. The caregiver can use these cues to optimize feeding by immediately responding to the infant’s needs (Shaker, 2013b).

Breastfeeding/Chestfeeding/Lactation

SLPs collaborate with parents, nurses, and lactation consultants prior to assessing feeding skills when appropriate. This requires a working knowledge of nursing strategies to facilitate safe and efficient swallowing.

Lactation assessment typically includes an evaluation of the following:

- the infant’s behavior (e.g., positive rooting, willingness to suckle)

- the infant’s position (e.g., well supported, tucked against the caregiver’s body)

- the infant’s ability to latch

- efficiency and coordination of the infant’s suck–swallow–breathe pattern

- health of the caregiver’s mammary tissue, if present

- the caregiver’s behavior (e.g., comfort with lactation, confidence in handling the infant, awareness of the infant’s cues during feeding)

For an example, see Community Management of Uncomplicated Acute Malnutrition in Infants < 6 Months of Age (C-MAMI) [PDF].

Bottle-Feeding

The assessment of bottle-feeding includes an evaluation of the following:

- the infant’s behavior (e.g., positive rooting, willingness to suckle)

- the infant’s readiness to accept a nipple

- the caregiver’s behavior while feeding the infant

- efficiency and coordination of the infant’s suck–swallow–breathe pattern

- nipple type and form of nutrition (breast milk or formula)

- the infant’s position

- quantity of intake

- the length of time the infant takes for one feeding

- the infant’s response to attempted interventions, such as

- a different nipple for flow control,

- external pacing,

- a different bottle to control air intake, and

- different positions (e.g., side feeding)

Spoon-Feeding

The assessment of spoon-feeding includes an evaluation of the optimal spoon type and the infant’s ability to

- move their head toward the spoon and then open their mouth,

- turn their head away from the spoon to show that they have had enough or are not interested,

- close their lips around the spoon for bolus extraction,

- clear food from the spoon with their top lip,

- move food from the spoon to the back of their mouth, and

- attempt to spoon-feed independently.

Clinical Evaluation: Toddlers, Preschoolers, and School-Age Children

The clinical evaluation of toddlers and preschool-age children typically includes the following (Arvedson, 2008):

- A thorough case history, including a review of family, medical, developmental, and feeding history

- A physical examination, including the parent–child dynamic; head, neck, and trunk mobility and positioning; cardiorespiratory status; overall state and response to sensory stimulation; and self-regulation

- A functional oral mechanism and cranial nerve examination

- A feeding assessment that replicates the home environment as closely as possible, such as

- the child seated in a highchair, a chair, or other specialized seating system as needed;

- offering textures and consistencies that are both familiar and preferred, in addition to varied, more challenging, and novel presentations;

- assessing for the effectiveness of both compensatory and active interventions for oral sensory and oral motor feeding needs;

- assessing stimulability for sensory motor–based interventions based on perceived deficits or trialing different utensils, cups, and so on; and/or

- providing caregiver training through psychosocial support and coaching to facilitate child-led, responsive mealtimes

Results of a clinical assessment are integrated to form a plan that answers the following questions:

- Are further referrals or testing, such as an instrumental swallowing evaluation, warranted?

- Can the child eat and drink orally in a way that meets nutrition and hydration needs?

- Are modifications needed in positioning, sensory aspects of foods and liquids, scheduling, or mealtime structure to facilitate success?

- What feeding skill–based deficits are suspected or present (motor)?

Clinical Evaluation: School Setting

Evaluation in the school setting includes students aged 3–21 years. The process may begin with a referral to a team of professionals within the school district trained in identifying and treating feeding and swallowing disorders. The referral can be initiated by families/caregivers or school personnel. In other cases, children may enter the school setting with a documented history of a feeding and swallowing disorder and prior or current treatment.

A physician’s order is typically not required to evaluate a student for feeding and swallowing disorder in the school setting; however, it is best practice to collaborate with the student’s physician, particularly if the student is medically fragile or under the care of a physician. See the School Collaboration With Outside Medical Professionals section below.

Parental/caregiver consent is required to initiate an evaluation in schools. Case history information is gathered from caregivers and via record review (e.g., videofluoroscopic swallowing study [VFSS] report, outpatient feeding team evaluation) about the child’s medical history, current health status, eating habits, and feeding or swallowing concerns.

The school-based SLP conducts the evaluation in collaboration with team members (OT, PT, school nurse), which includes observation of the student eating a typical meal or snack. Implementation of strategies and modifications is part of the diagnostic process. Trials of specific interventions may be warranted based on the assessment findings.

A feeding and swallowing evaluation includes a determination of a child’s ability to eat and drink enough food safely within the school’s mealtime schedule. Not being able to eat within the allotted time can decrease a child’s ability to access the curriculum. SLPs make recommendations for accommodations such as extended mealtimes or shorter, more frequent meals. Consideration of inclusive time and impact on peer interactions should be considered.

Additional components of the evaluation include the following:

- An assessment of oral structures and function during intake

- An assessment to determine the developmental level of feeding skills

- An assessment of various textures and consistencies of food to assess oral sensory and oral motor feeding skills

- An assessment to determine the effectiveness of both compensatory and active interventions for oral sensory and oral motor feeding needs

- An assessment of issues related to fatigue and access to adequate levels of nutrition and hydration during school

- An assessment of oral feeding abilities, including the ability to manipulate and propel the bolus, and effective mastication

- An assessment for any signs of feeding and swallowing concerns, including coughing, choking, prolonged mastication time, oral holding, wet vocal quality, or congestion

- An assessment of adaptive equipment for eating and positioning by an OT and a PT

- An assessment to determine the effectiveness of accommodations to reduce the educational impact of feeding and swallowing disorders

- An assessment to determine the impact of feeding and swallowing on inclusive time

Team Approach

The school-based feeding and swallowing team includes professionals within the school setting and works closely with families in all phases of evaluation and treatment. Professionals who treat the child outside of the school setting (e.g., physicians, dietitians, psychologists) are consulted to collaborate and share information (with parental consent). See the School Collaboration With Outside Medical Professionals section below.

Members of the team include, but are not limited to, the following:

- SLP

- family/caregiver

- classroom teacher and assistant

- school nurse

- dietitian and/or cafeteria staff

- OT

- PT

- school administrator

- behavioral specialist

- school psychologist

- social worker

The team works together to

- develop an individualized health plan that includes compensatory strategies, food and drink consistency recommendations, and emergency procedures for choking;

- provide information and training to staff and families for compensatory strategies;

- develop an individualized education program (IEP) to include goals and accommodations needed for safe feeding and swallowing;

- oversee the day-to-day implementation of the feeding and swallowing plan and any individualized education program strategies to help prevent aspiration, choking, undernutrition, or dehydration while in school;

- identify and provide direct treatment for feeding and swallowing if an adverse impact on educational or functional performance is found to be present (IDEA, 2004); and

- work with families to seek physician referral for instrumental assessment and/or follow-up as needed.

School Collaboration With Outside Medical Professionals

Best practice indicates establishing open lines of communication with the student’s physician or other health care provider—either through the caregiver or directly—with the caregiver’s consent. Any communication by the school team to an outside physician, facility, or individual requires signed parental consent.

A physician’s order or prescription is not required to perform clinical evaluations, modify diets, or provide intervention in the school setting. However, there are times when a prescription, referral, or medical clearance from the student’s primary care physician or other health care provider is indicated, such as when the student

- receives part or all of their nutrition or hydration via enteral or parenteral tube feeding,

- has a complex medical condition and experiences a significant change in status,

- has recently been hospitalized with aspiration pneumonia,

- has had a recent choking incident and has required emergency care,

- is suspected of having aspirated food or liquid into the lungs,

- has suspected structural abnormalities (requires an assessment from a medical professional), and/or

- requires modification of their school-provided meals (see the U.S. Department of Agriculture guidance discussed in the School Setting Considerations section above).

See ASHA’s resources on interprofessional education/interprofessional practice (IPE/IPP) and collaboration and teaming for guidance on successful collaborative service delivery across settings.

See the Treatment in the School Setting section below for further information.

Instrumental Evaluation

Instrumental evaluation is conducted after a clinical evaluation when more information is needed to determine the presence and pathophysiology of dysphagia. Instrumental assessments can help provide specific information about anatomy and physiology otherwise not accessible by noninstrumental evaluation. Instrumental evaluation identifies the appropriate treatment plan based on swallowing physiology and can also help determine if swallow safety can be improved with strategies such as modifying food textures, liquid consistencies, and positioning.

Instrumental evaluation is completed in a medical setting. These studies are a team effort and may include the radiologist, radiology technician, and SLP. The SLP or radiology technician typically prepares and presents the barium items, whereas the radiologist records the swallow for visualization and analysis. Please see ASHA’s resource on state instrumental assessment requirements for further details.

The two most commonly used instrumental evaluations of swallowing for the pediatric population are

The roles of the SLP in the instrumental evaluation of swallowing and feeding disorders include

- participating in decisions regarding the appropriateness of these procedures;

- conducting the VFSS and FEES instrumental procedures;

- interpreting and applying data from instrumental evaluations to

- determine the severity and nature of the swallowing disorder and the child’s potential for safe oral feeding

- develop feeding and swallowing treatment plans, including recommendations for optimal feeding techniques;

- being familiar with and using information from various diagnostic procedures that give information related to swallowing, including

- manofluorography,

- scintigraphy (which, in the pediatric population, may also be referred to as “radionuclide milk scanning”),

- pharyngeal manometry,

- 24-hour pH monitoring,

- flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy (usually completed in the office),

- direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy (usually completed in the operating room), and

- esophagoscopy.

General Considerations for Instrumental Evaluations

Determining the appropriate procedure to use depends on what needs to be visualized and which procedure will be best tolerated by the child. Prior to the instrumental evaluation, clinicians may consult with the team to coordinate feeding schedules that will maximize feeding readiness during the evaluation.

Examinations should be completed only for infants or children when (Martin-Harris et al., 2020)

- there are documented or suspected oropharyngeal swallowing impairments,

- the patient is medically stable and has the skills needed to participate, and

- the findings are needed to determine the plan of care.

These points should also be considered when planning for repeat instrumental exams, which should not be completed at arbitrary time intervals but rather dictated by a change in status or the need for new information, understanding the cumulative effects of radiation exposure over the lifespan for infants and young children (Martin-Harris et al., 2020). When conducting an instrumental evaluation, SLPs should consider the following:

- Infants are obligate nasal breathers, and the placement of a flexible endoscope in one nostril when a nasogastric tube is in the other nostril could compromise breathing. Clinicians should discuss this with the medical team to determine options, including the temporary removal of the feeding tube and/or use of another means of swallowing assessment.

- Anxiety and crying are common reactions. Anxiety may be reduced by using distractions (e.g., preferred toys, videos), allowing the child to sit on the parent’s or the caregiver’s lap (for FEES procedures), and decreasing the number of observers in the room.

- Positioning for the VFSS depends on the size of the child and their medical condition (Arvedson & Lefton-Greif, 1998; Geyer & McGowan, 1995). Infants under 6 months old typically require head, neck, and trunk support.

- Children are positioned as they are typically fed at home and in a manner that avoids spontaneous or reflexive movements that could reduce safety. Modifications to positioning are made as needed and are documented as part of the assessment findings.

- Any study in which a natural feeding process is impossible may not represent typical swallow function and should be interpreted with caution. Disruptions to the natural feeding process include

- inappropriate positioning,

- lack of caregiver involvement, and

- the use of unfamiliar foods.

Test Environment

Procedures take place in a child-friendly environment if possible and appropriate. They can involve toys, visual distractors, rewards, and a familiar caregiver. Various items are available in the room to promote success and to simulate a typical mealtime experience. Such items include preferred foods, familiar food containers, utensil options, and seating options.

Preparing the Child and Family

The clinician prepares the child and family by

- explaining the procedure, its purpose, and the test environment in a health-literate way;

- implementing a trauma-informed care approach that allows the child to be calm and get used to the room, the equipment, and the professionals who will be present;

- instructing the family to schedule meals and snacks so that the child will be hungry and more likely to accept foods needed for the study, as appropriate;

- collaborating with interprofessional team members, such as child life specialists, to support the child and their caregivers before, during, and after the exam; and

- asking the family to provide familiar utensils, preferred foods, and specialized seating from home to make the environment as natural as possible and increase the child’s comfort.

Tube Feeding

Tube feeding, also known as enteral nutrition, is used when nutrition cannot be maintained through oral intake. Types of tubes include the following:

- nasogastric (passed through the nose down the esophagus and into the stomach)

- transpyloric (placed in the duodenum or jejunum)

- gastrostomy (a tube placed in the stomach)

- gastronomy–jejunostomy (placed in the jejunum)

Alternative feeding does not preclude the need for feeding-related treatment. These approaches may be considered by the medical team if the child’s swallowing safety and efficiency cannot reach a level of adequate function or does not adequately support nutrition and hydration. In these instances, the swallowing and feeding team considers

- the optimum tube-feeding method that best meets the child’s needs and

- whether the child will need tube feeding for a short or an extended period of time.

SLPs do not make medical decisions regarding enteral feeding. However, information provided by SLPs may contribute to medical providers’ decision-making process. Please see ASHA’s resource on alternative nutrition and hydration in dysphagia care for further information.

See the Treatment section of the Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

The primary goals of feeding and swallowing intervention for children are to

- support safe and adequate nutrition and hydration;

- determine the optimum feeding methods and techniques to maximize swallowing safety and feeding efficiency;

- incorporate dietary preferences by collaborating with caregivers;

- help individuals achieve age-appropriate eating skills in the most normal setting and manner possible (i.e., eating meals with peers in the school, mealtime with the family);

- minimize the risk of pulmonary complications;

- maximize the quality of life;

- support caregiver–child interactions and encourage child and caregiver autonomy and independence; and

- prevent future feeding issues with positive feeding-related experiences to the extent possible, given the child’s medical situation.

Medical, surgical, and nutritional factors are important considerations in treatment planning. The underlying disease state(s), the chronological and developmental age of the child, social and environmental factors, and psychological and behavioral factors also affect treatment recommendations. Not every child will have the same access to food, health care providers, or other resources that are necessary to comply with recommendations. Clinicians take each patient’s and caregiver’s unique circumstances into account when providing education, counseling, and community resource recommendations. See ASHA’s resource on social determinants of health for further information.

An interdisciplinary team approach is essential for individualized treatment of children with complex feeding problems (McComish et al., 2016; West, 2024). See ASHA’s resources on interprofessional education/interprofessional practice (IPE/IPP) and collaboration and teaming.

Questions to ask when developing an appropriate treatment plan include the following:

Can the child eat and drink safely?

Consider the child’s overall swallowing function and how these factors affect feeding efficiency and safety, as follows:

- pulmonary status

- nutritional status

- overall medical condition

- physical mobility, positioning, and their influence on overall health

- feeding and swallowing abilities

- cognition

Can the child receive adequate nutrition and hydration by mouth alone, given length of time to eat, efficiency, and fatigue factors?

This question is answered by the child’s interprofessional team. If the child cannot meet nutritional needs by mouth, the team may make recommendations for nonoral intake and/or the inclusion of dietary supplements.

How can the child’s functional abilities be maximized?

This might involve questions and decisions about what the child’s current skill level is, if the child can safely eat an oral diet that meets nutritional needs, if that diet needs to be modified in any way, and if the child needs compensatory strategies to eat the diet. Does the child have the potential to improve swallowing function with direct treatment?

How can the child’s quality of life be preserved and/or enhanced?

The family’s customs and traditions around mealtimes and food should be respected and incorporated into therapy recommendations and education. Caregivers may prioritize the following quality-of-life concerns (Simione et al., 2020):

- enjoyable stress-free mealtimes

- eating without medical interventions (e.g., tube feedings)

- health-related outcomes

- expanding the child’s diet

- eating healthy foods

- meeting nutritional needs

- maintaining or gaining weight

See also Simione et al. (2023).

What are the family’s preferences and goals, and how does the family dynamic influence mealtimes?

Are the family’s expectations congruent with the child’s current developmental age and skill set? Does the family use a responsive feeding approach, attending to the child’s hunger and satiety cues and respond in a supportive manner? Are there other psychosocial factors that require support from other interprofessional practice team members, such as a mental health practitioner?

Treatment Considerations

The health and well-being of the child is the primary concern in treating pediatric feeding and swallowing disorders. Beliefs about the medicinal value of some foods or liquids vary among cultures, religions, and individual families. Some beliefs and healing practices may not be consistent with recommendations that an SLP typically makes. The clinician works with the family to determine alternatives that promote safety while aligning with their culture, beliefs, and customs around food.

Appropriate treatment approaches consider the child’s age, cognitive and physical abilities, and specific swallowing and feeding problems. Infants, young children, and children with an intellectual disability or language disorder may have difficulty following verbal or nonverbal directions. In these cases, intervention might consist of changes in the environment or caregiver training for improving safety and efficiency of feeding.

The management of feeding and swallowing disorders in infants, toddlers, and older children is facilitated by a multidisciplinary approach. This is especially important for children with complex medical conditions.

Treatment considers the following:

- Readiness for oral feeding—Children who are beginning to eat orally for the first time or after an extended period of nonoral feeding will need time to become comfortable in the presence of food and to explore food without experiencing physiological responses (e.g., for children with significant gastrointestinal problems).

- Communication—SLPs can help caregivers understand emerging communication and interpret their behavior as it relates to feeding and swallowing while also providing language stimulation related to food vocabulary (e.g., names of foods and various flavors) as well as how children might be using feeding behaviors (e.g., food refusal responses) to communicate.

- Physical conditions—Treatment for children with conditions and disorders that affect movement (e.g., cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy) needs to consider the length of time to fatigue, optimal feeding methods, and positioning to maximize safe feeding and swallowing.

Compensatory Treatment

Postural and Positioning Techniques

Postural and positioning techniques involve adjusting the child’s posture or position to increase feeding safety. These techniques serve to protect the airway and support functional transit of food and liquid. No single posture works for all people. Postural changes differ between infants and older children. Instrumental assessments provide necessary information regarding the effectiveness of any of the techniques of swallow safety, which include the following:

- chin down—tucking the chin down toward the neck

- chin up—slightly tilting the head up

- head rotation—turning the head to the weak side to protect the airway

- upright positioning—supports the head, neck, and trunk alignment in a way that is functional considering the child’s physical needs

- head stabilization—supported so as to present in a chin-neutral position

- reclining position—using pillow support or a reclined infant seat with trunk and head support

- side-lying positioning (for infants)

Diet Modifications

Diet modifications are any changes made to the viscosity, texture, temperature, portion size, or taste of foods or liquids to increase safety and decrease difficulty of swallowing. Typical modifications may include thickening thin liquids, softening, cutting/chopping, or pureeing solid foods. Taste or temperature of a food may be changed to increase sensory input for swallowing. See the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI).

Diet modifications include individual and family preferences whenever feasible. SLPs consult with families regarding safety of medical treatments, such as swallowing medication in liquid or pill form, which may be contraindicated by the disorder. Diet modifications should consider the nutritional needs of the child and be guided by clinical and instrumental assessment findings.

Precautions

Consumers should use caution regarding the use of commercial, gum-based thickeners for infants of any age (Beal et al., 2012; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2017). SLPs should be aware of these precautions and consult, as appropriate, with their facility to develop guidelines for using thickened liquids with infants (Gosa, Dodrill, & Robbins, 2020).

Equipment and Utensils

Adaptive equipment and utensils may be used with children who have feeding problems to foster independence with eating and increase swallow safety. These tools can help by controlling bolus size or achieving the optimal flow rate of liquids.

Examples of adaptive equipment include the following:

- modified nipples

- cutout cups

- weighted forks and spoons

- angled forks and spoons

- sectioned plates

- non-tip bowls

- Dycem® to prevent plates and cups from sliding

- metered straws

- feeder-assisted straw cups

SLPs work with oral and pharyngeal implications of adaptive equipment. SLPs may collaborate with occupational therapists, because motor control is an important consideration for using adaptive equipment.

Direct Interventions

Swallowing Maneuvers

Swallowing maneuvers are strategies used to change the timing or strength of movements of swallowing (Logemann, 2000). Some maneuvers require following multistep directions and may not be appropriate for young children and/or older children with cognitive impairments. Please see the Treatment section of ASHA’s Practice Portal page on Adult Dysphagia for further information. Examples of maneuvers include the following:

- Effortful swallow—Posterior tongue base movement is increased to facilitate bolus clearance.

- Mendelsohn maneuver—Elevation of the larynx is voluntarily prolonged at the peak of the swallow to help the bolus pass more efficiently through the pharynx and to prevent food/liquid from falling into the airway.

- Supraglottic swallow—Vocal folds are closed by voluntarily holding one’s breath before and during the swallow in order to protect the airway.

- Super-supraglottic swallow—An effortful breath hold tilts the arytenoid forward, which closes the airway entrance before and during the swallow.

Although sometimes referred to as the Masako maneuver, the Masako (or “tongue-hold”) is considered an exercise, not a maneuver. In the Masako, the tongue is held forward between the teeth while swallowing; this is performed without food or liquid in the mouth to prevent coughing or choking.

Swallowing maneuvers and other rehabilitation techniques commonly utilized in adult populations have limited application in pediatric populations due to physical and cognitive immaturity of infants and children (Gosa & Dodrill, 2017).

Oral Motor Treatments and Sensory Techniques

There is limited high-quality evidence supporting the use of oral motor exercises or sensory techniques in the treatment of pediatric feeding disorder–related sensory deficits and swallowing dysfunction in isolation (Arvedson et al., 2010; Gosa et al., 2017; Gosa & Dodrill, 2017). Motor learning is experience dependent, meaning that children establish motor patterns through opportunities that are frequent and are as closely related to the desired task as possible (Kleim & Jones, 2008; Zimmerman et al., 2020). For example, if a child wants to chew a banana, they should be provided with frequent opportunities and modifications that encourage them to engage in the motor task of chewing a banana. As compared with oral motor exercises, modifying the sensory components of food-like taste, texture, temperature, and shape is more effective as facilitating desired oral motor patterns, such as chewing or tongue lateralization (Arvedson et al., 2010).

Evidence-based practice is a guiding principle of speech-language pathology. Clinicians should consider any available evidence before using any product or technique. See ASHA’s Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) page, and visit ASHA’s Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Evidence Map for further information.

Infant Feeding Strategies

Pacing

Pacing involves decreasing the rate of eating by controlling the rate of presentation of the food or liquid and the time between bites or swallows. Feeding strategies for children may include alternating bites of food with sips of liquid or swallowing two to three times per bite or sip. For infants, pacing involves limiting the number of consecutive sucks. Strategies that slow the feeding rate may allow for more time between swallows to clear the bolus and may support more timely breaths.

Flow Rate Modifications

Nipple flow rate selection is one of the most important considerations for keeping the airway safe during bottle-feeding. Using a slower flow nipple can support and regulate suck–swallow–breathe coordination (Goldfield et al., 2013). Bottle nipple manufacturing is an unregulated industry. Therefore, there can be high performance variability between brands and sometimes between individual nipples. This variability can also be altered by external variables such as infant sucking pressures, pliability, hydrostatic pressure, and viscosity modifications (Pados, 2021).

Elevated Side-Lying Positioning

Elevated side-lying positioning aims to support better bolus control and reduce the work of breathing (Girgin et al., 2018; Park et al., 2014; Raczyńska et al., 2022). The infant is positioned on their side, with the head, shoulders, and hips neutrally aligned and facing upward and elevated to approximately 45 degrees. Flexion is provided through swaddling.

Viscosity Modifications (Thickening)

Thickening may be necessary to treat dysphagia for some infants, based on the results of an instrumental assessment. The goals of thickening agents are to

- establish safe oral feeding that is least disruptive to developing feeding skills and

- reduce and stop using a thickener as quickly as possible.

There is limited evidence about the effects of viscosity modifications, or thickening, as an intervention for dysphagia in infants (Gosa et al., 2011). Some anecdotal data link some thickened liquids and harmful side effects (Beal et al., 2012; Clarke & Robinson, 2004). The interprofessional team discusses the risks and benefits of viscosity modifications as well as the infant’s unique comorbidities, health status, and parent preferences (Duncan et al., 2019).

Cue-Based Feeding

Cue-based feeding is an approach that views the feeding experience as a partnership with the infant. The infant’s cues are viewed as communication that guides the caregiver and allows the infant to set the pace of feeding and have more opportunity to enjoy the experience of feeding when the quality of feeding is prioritized over the quantity ingested. As a result, intake may be improved (Shaker, 2013a).

The infant’s cues during feeding, such as lack of active sucking, passivity, or pushing away, provide information about the infant’s physiologic stability during feeding and inform the feeder’s response to cues, which allows them to provide immediate intervention to support positive oral feeding experiences. Cue-based feeding is an approach that is predominantly used in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU); however, knowing that motor learning is experience dependent, a trauma-informed, cue-based approach to oral feeding can be adapted and is appropriate for clinicians working with infants and their families in other settings.

SLPs in the NICUs educate caregivers to improve their understanding of and response to the infant’s communication during feeding. Most NICUs have begun to move away from volume-driven feeding to cue-based feeding (Gosa & Dodrill, 2023; Shaker, 2013a).

Responsive Feeding

Like cue-based feeding, responsive feeding focuses on the caregiver-and-child dynamic. Responsive feeders attempt to understand and read a child’s cues for both hunger and satiety; respect that communication in a nurturing, reciprocal way; and support the child in developing preferences for age-appropriate, nutritionally balanced foods. Responsive feeding encourages the child to eat autonomously, in response to their developmental and physiologic needs, which supports self-regulation and cognitive, emotional, and social development (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2021).

Biofeedback

Biofeedback treatment for swallowing uses instrumental methods (e.g., surface electromyography, ultrasound, nasendoscopy) to give visual feedback during feeding and swallowing. Children with sufficient cognitive skills can be taught to interpret this visual information and make physiological changes during the swallowing process.

Electrical Stimulation

Electrical stimulation uses an electrical current to stimulate the peripheral nerve. SLPs with appropriate training and competence in performing electrical stimulation may provide the intervention. ASHA does not require any additional certifications to perform electrical stimulation and urges members to follow the ASHA Code of Ethics, Principle II, Rule A, which states: “Individuals who hold the Certificate of Clinical Competence shall engage in only those aspects of the professions that are within the scope of their professional practice and competence, considering their certification status, education, training, and experience” (ASHA, 2023).

There is concern that using neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) with neonates and infants may impact neuromuscular development in ways that are not yet well understood. Clinicians should use discretion when considering using NMES to minimize potential harm to patients (Epperson & Sandage, 2019). High-risk infants may exhibit dampened responses or cues to pain, and that pairing the potentially painful experience of NMES with feeding may affect neuromuscular development and increase aversion to feeding by pairing a painful stimulus with swallowing (Bustamante et al., 2022). ASHA is strongly committed to evidence-based practice and urges members to consider the best available evidence before using any product or technique.

Please see the NMES section of the Pediatric Feeding and Swallowing Evidence Map for further information.

Intraoral Prosthetics and Appliances

Intraoral prosthetics (e.g., palatal obturator, palatal lift prosthesis) can be used to stabilize the intraoral cavity by providing compensation or physical support for children with congenital abnormalities (e.g., cleft palate) or damage to the oropharyngeal mechanism. This support may help improve swallowing efficiency and function.

Intraoral appliances (e.g., palatal plates) are removable devices with small knobs that provide tactile stimulation inside the mouth to encourage lip closure and appropriate lip and tongue position for improved functional feeding skills. Referrals may be made to dental professionals for assessment and fitting of these devices.

Treatment in the School Setting

SLPs who address feeding and swallowing in schools should be familiar with IDEA, which protects students with disabilities. This includes students with feeding and swallowing disorders. School-based treatment addresses the impact of the disorder on a student’s educational performance to promote swallow safety for adequate hydration and nutrition. Maximizing the health of the students is key to facilitating their academic progress and access to the educational curriculum. Goals are implemented through individualized education programs (IEPs) written specifically for the students’ individual needs.

Individualized Education Program (IEP)

Information from the referral, caregiver interview/case history, and clinical evaluation of the student is used to develop IEP goals and objectives for improved feeding and swallowing, if appropriate. The IEP may include direct therapy aimed at improving oral feeding and swallowing skills, in addition to accommodations needed for safe and efficient oral intake throughout the school day.

Feeding and Swallowing Plan

A feeding and swallowing plan addresses diet and environmental modifications and procedures to minimize aspiration and choking risks while optimizing nutrition and hydration. Ongoing staff and family education is essential to student safety. The plan should be reviewed annually along with the IEP goals and objectives or sooner if significant changes occur or if it is found to be ineffective.

A feeding and swallowing plan may include, but not be limited to, the following:

- student demographic information

- appropriate positioning of the student for a safe oral intake

- specialized equipment indicated for positioning or feeding, as needed