Speech Sound Disorders-Articulation and Phonology

See the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for summaries of the available research on this topic.

The scope of this page is speech sound disorders with no known cause—historically called articulation and phonological disorders—in preschool and school-age children (ages 3–21).

Information about speech sound problems related to motor/neurological disorders, structural abnormalities, and sensory/perceptual disorders (e.g., hearing loss) is not addressed in this page.

See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Childhood Apraxia of Speech and Cleft Lip and Palate for information about speech sound problems associated with these two disorders. A Practice Portal page on dysarthria in children will be developed in the future.

Speech Sound Disorders

Speech sound disorders is an umbrella term referring to any difficulty or combination of difficulties with perception, motor production, or phonological representation of speech sounds and speech segments—including phonotactic rules governing permissible speech sound sequences in a language.

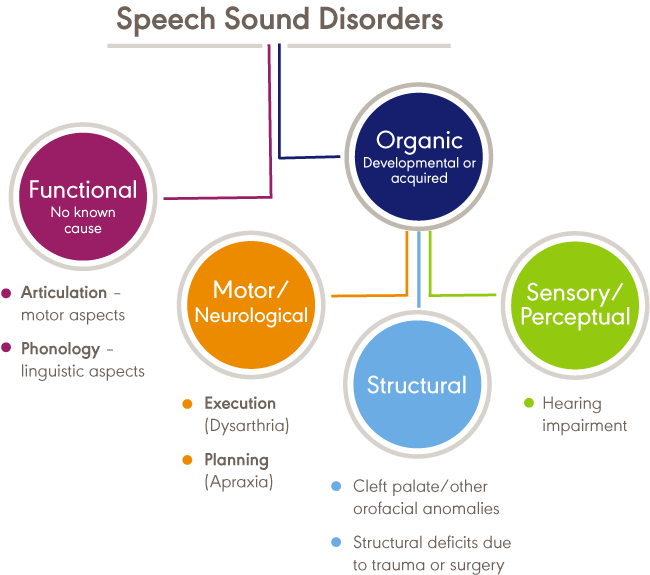

Speech sound disorders can be organic or functional in nature. Organic speech sound disorders result from an underlying motor/neurological, structural, or sensory/perceptual cause. Functional speech sound disorders are idiopathic—they have no known cause. See figure below.

Organic Speech Sound Disorders

Organic speech sound disorders include those resulting from motor/neurological disorders (e.g., childhood apraxia of speech and dysarthria), structural abnormalities (e.g., cleft lip/palate and other structural deficits or anomalies), and sensory/perceptual disorders (e.g., hearing loss).

Functional Speech Sound Disorders

Functional speech sound disorders include those related to the motor production of speech sounds and those related to the linguistic aspects of speech production. Historically, these disorders are referred to as articulation disorders and phonological disorders, respectively. Articulation disorders focus on errors (e.g., distortions and substitutions) in production of individual speech sounds. Phonological disorders focus on predictable, rule-based errors (e.g., fronting, stopping, and final consonant deletion) that affect more than one sound. It is often difficult to cleanly differentiate between articulation and phonological disorders; therefore, many researchers and clinicians prefer to use the broader term, "speech sound disorder," when referring to speech errors of unknown cause. See Bernthal, Bankson, and Flipsen (2017) and Peña-Brooks and Hegde (2015) for relevant discussions.

This Practice Portal page focuses on functional speech sound disorders. The broad term, "speech sound disorder(s)," is used throughout; articulation error types and phonological error patterns within this diagnostic category are described as needed for clarity.

Procedures and approaches detailed in this page may also be appropriate for assessing and treating organic speech sound disorders. See Speech Characteristics: Selected Populations [PDF] for a brief summary of selected populations and characteristic speech problems.

The incidence of speech sound disorders refers to the number of new cases identified in a specified period. The prevalence of speech sound disorders refers to the number of children who are living with speech problems in a given time period.

Estimated prevalence rates of speech sound disorders vary greatly due to the inconsistent classifications of the disorders and the variance of ages studied. The following data reflect the variability:

- Overall, 2.3% to 24.6% of school-aged children were estimated to have speech delay or speech sound disorders (Black, Vahratian, & Hoffman, 2015; Law, Boyle, Harris, Harkness, & Nye, 2000; Shriberg, Tomblin, & McSweeny, 1999; Wren, Miller, Peters, Emond, & Roulstone, 2016).

- A 2012 survey from the National Center for Health Statistics estimated that, among children with a communication disorder, 48.1% of 3- to 10-year old children and 24.4% of 11- to 17-year old children had speech sound problems only. Parents reported that 67.6% of children with speech problems received speech intervention services (Black et al., 2015).

- Residual or persistent speech errors were estimated to occur in 1% to 2% of older children and adults (Flipsen, 2015).

- Reports estimated that speech sound disorders are more prevalent in boys than in girls, with a ratio ranging from 1.5:1.0 to 1.8:1.0 (Shriberg et al., 1999; Wren et al., 2016).

- Prevalence rates were estimated to be 5.3% in African American children and 3.8% in White children (Shriberg et al., 1999).

- Reports estimated that 11% to 40% of children with speech sound disorders had concomitant language impairment (Eadie et al., 2015; Shriberg et al., 1999).

- Poor speech sound production skills in kindergarten children have been associated with lower literacy outcomes (Overby, Trainin, Smit, Bernthal, & Nelson, 2012). Estimates reported a greater likelihood of reading disorders (relative risk: 2.5) in children with a preschool history of speech sound disorders (Peterson, Pennington, Shriberg, & Boada, 2009).

Signs and symptoms of functional speech sound disorders include the following:

- omissions/deletions—certain sounds are omitted or deleted (e.g., "cu" for "cup" and "poon" for "spoon")

- substitutions—one or more sounds are substituted, which may result in loss of phonemic contrast (e.g., "thing" for "sing" and "wabbit" for "rabbit")

- additions—one or more extra sounds are added or inserted into a word (e.g., "buhlack" for "black")

- distortions—sounds are altered or changed (e.g., a lateral "s")

- syllable-level errors—weak syllables are deleted (e.g., "tephone" for "telephone")

Signs and symptoms may occur as independent articulation errors or as phonological rule-based error patterns (see ASHA's resource on selected phonological processes [patterns] for examples). In addition to these common rule-based error patterns, idiosyncratic error patterns can also occur. For example, a child might substitute many sounds with a favorite or default sound, resulting in a considerable number of homonyms (e.g., shore, sore, chore, and tore might all be pronounced as door; Grunwell, 1987; Williams, 2003a).

Influence of Accent

An accent is the unique way that speech is pronounced by a group of people speaking the same language and is a natural part of spoken language. Accents may be regional; for example, someone from New York may sound different than someone from South Carolina. Foreign accents occur when a set of phonetic traits of one language are carried over when a person learns a new language. The first language acquired by a bilingual or multilingual individual can influence the pronunciation of speech sounds and the acquisition of phonotactic rules in subsequently acquired languages. No accent is "better" than another. Accents, like dialects, are not speech or language disorders but, rather, only reflect differences. See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Multilingual Service Delivery in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology and Cultural Responsiveness.

Influence of Dialect

Not all sound substitutions and omissions are speech errors. Instead, they may be related to a feature of a speaker's dialect (a rule-governed language system that reflects the regional and social background of its speakers). Dialectal variations of a language may cross all linguistic parameters, including phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. An example of a dialectal variation in phonology occurs with speakers of African American English (AAE) when a "d" sound is used for a "th" sound (e.g., "dis" for "this"). This variation is not evidence of a speech sound disorder but, rather, one of the phonological features of AAE.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) must distinguish between dialectal differences and communicative disorders and must

- recognize all dialects as being rule-governed linguistic systems;

- understand the rules and linguistic features of dialects represented by their clientele; and

- be familiar with nondiscriminatory testing and dynamic assessment procedures, such as identifying potential sources of test bias, administering and scoring standardized tests using alternative methods, and analyzing test results in light of existing information regarding dialect use (see, e.g., McLeod, Verdon, & The International Expert Panel on Multilingual Children's Speech, 2017).

See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Multilingual Service Delivery in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology and Cultural Responsiveness.

The cause of functional speech sound disorders is not known; however, some risk factors have been investigated.

Frequently reported risk factors include the following:

- Gender—the incidence of speech sound disorders is higher in males than in females (e.g., Everhart, 1960; Morley, 1952; Shriberg et al., 1999).

- Pre- and perinatal problems—factors such as maternal stress or infections during pregnancy, complications during delivery, preterm delivery, and low birthweight were found to be associated with delay in speech sound acquisition and with speech sound disorders (e.g., Byers Brown, Bendersky, & Chapman, 1986; Fox, Dodd, & Howard, 2002).

- Family history—children who have family members (parents or siblings) with speech and/or language difficulties were more likely to have a speech disorder (e.g., Campbell et al., 2003; Felsenfeld, McGue, & Broen, 1995; Fox et al., 2002; Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1994).

- Persistent otitis media with effusion—persistent otitis media with effusion (often associated with hearing loss) has been associated with impaired speech development (Fox et al., 2002; Silva, Chalmers, & Stewart, 1986; Teele, Klein, Chase, Menyuk, & Rosner, 1990).

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) play a central role in the screening, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of persons with speech sound disorders. The professional roles and activities in speech-language pathology include clinical/educational services (diagnosis, assessment, planning, and treatment); prevention and advocacy; and education, administration, and research. See ASHA's Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology (ASHA, 2016).

Appropriate roles for SLPs include the following:

- Providing prevention information to individuals and groups known to be at risk for speech sound disorders, as well as to individuals working with those at risk

- Educating other professionals on the needs of persons with speech sound disorders and the role of SLPs in diagnosing and managing speech sound disorders

- Screening individuals who present with speech sound difficulties and determining the need for further assessment and/or referral for other services

- Recognizing that students with speech sound disorders have heightened risks for later language and literacy problems

- Conducting a culturally and linguistically relevant comprehensive assessment of speech, language, and communication

- Taking into consideration the rules of a spoken accent or dialect, typical dual-language acquisition from birth, and sequential second-language acquisition to distinguish difference from disorder

- Diagnosing the presence or absence of a speech sound disorder

- Referring to and collaborating with other professionals to rule out other conditions, determine etiology, and facilitate access to comprehensive services

- Making decisions about the management of speech sound disorders

- Making decisions about eligibility for services, based on the presence of a speech sound disorder

- Developing treatment plans, providing intervention and support services, documenting progress, and determining appropriate service delivery approaches and dismissal criteria

- Counseling persons with speech sound disorders and their families/caregivers regarding communication-related issues and providing education aimed at preventing further complications related to speech sound disorders

- Serving as an integral member of an interdisciplinary team working with individuals with speech sound disorders and their families/caregivers (see ASHA's resource on interprofessional education/interprofessional practice [IPE/IPP])

- Consulting and collaborating with professionals, family members, caregivers, and others to facilitate program development and to provide supervision, evaluation, and/or expert testimony (see ASHA's resource on focusing care on individuals and their care partners)

- Remaining informed of research in the area of speech sound disorders, helping advance the knowledge base related to the nature and treatment of these disorders, and using evidence-based research to guide intervention

- Advocating for individuals with speech sound disorders and their families at the local, state, and national levels

As indicated in the Code of Ethics (ASHA, 2023), SLPs who serve this population should be specifically educated and appropriately trained to do so.

See the Assessment section of the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

Screening

Screening is conducted whenever a speech sound disorder is suspected or as part of a comprehensive speech and language evaluation for a child with communication concerns. The purpose of the screening is to identify individuals who require further speech-language assessment and/or referral for other professional services.

Screening typically includes

- screening of individual speech sounds in single words and in connected speech (using formal and or informal screening measures);

- screening of oral motor functioning (e.g., strength and range of motion of oral musculature);

- orofacial examination to assess facial symmetry and identify possible structural bases for speech sound disorders (e.g., submucous cleft palate, malocclusion, ankyloglossia); and

- informal assessment of language comprehension and production.

See ASHA's resource on assessment tools, techniques, and data sources.

Screening may result in

- recommendation to monitor speech and rescreen;

- referral for multi-tiered systems of support such as response to intervention (RTI);

- referral for a comprehensive speech sound assessment;

- recommendation for a comprehensive language assessment, if language delay or disorder is suspected;

- referral to an audiologist for a hearing evaluation, if hearing loss is suspected; and

- referral for medical or other professional services, as appropriate.

Comprehensive Assessment

The acquisition of speech sounds is a developmental process, and children often demonstrate "typical" errors and phonological patterns during this acquisition period. Developmentally appropriate errors and patterns are taken into consideration during assessment for speech sound disorders in order to differentiate typical errors from those that are unusual or not age appropriate.

The comprehensive assessment protocol for speech sound disorders may include an evaluation of spoken and written language skills, if indicated. See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Spoken Language Disorders and Written Language Disorders.

Assessment is accomplished using a variety of measures and activities, including both standardized and nonstandardized measures, as well as formal and informal assessment tools. See ASHA's resource on assessment tools, techniques, and data sources.

SLPs select assessments that are culturally and linguistically sensitive, taking into consideration current research and best practice in assessing speech sound disorders in the languages and/or dialect used by the individual (see, e.g., McLeod et al., 2017). Standard scores cannot be reported for assessments that are not normed on a group that is representative of the individual being assessed.

SLPs take into account cultural and linguistic speech differences across communities, including

- phonemic and allophonic variations of the language(s) and/or dialect(s) used in the community and how those variations affect determination of a disorder or a difference and

- differences among speech sound disorders, accents, dialects, and patterns of transfer from one language to another. See phonemic inventories and cultural and linguistic information across languages.

Consistent with the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework (ASHA, 2016a; WHO, 2001), a comprehensive assessment is conducted to identify and describe

- impairments in body structure and function, including underlying strengths and weaknesses in speech sound production and verbal/nonverbal communication;

- co-morbid deficits or conditions, such as developmental disabilities, medical conditions, or syndromes;

- limitations in activity and participation, including functional communication, interpersonal interactions with family and peers, and learning;

- contextual (environmental and personal) factors that serve as barriers to or facilitators of successful communication and life participation; and

- the impact of communication impairments on quality of life of the child and family.

See ASHA's Person-Centered Focus on Function: Speech Sound Disorder [PDF] for an example of assessment data consistent with ICF.

Assessment may result in

- diagnosis of a speech sound disorder;

- description of the characteristics and severity of the disorder;

- recommendations for intervention targets;

- identification of factors that might contribute to the speech sound disorder;

- diagnosis of a spoken language (listening and speaking) disorder;

- identification of written language (reading and writing) problems;

- recommendation to monitor reading and writing progress in students with identified speech sound disorders by SLPs and other professionals in the school setting;

- referral for multi-tiered systems of support such as response to intervention (RTI) to support speech and language development; and

- referral to other professionals as needed.

Case History

The case history typically includes gathering information about

- the family's concerns about the child's speech;

- history of middle ear infections;

- family history of speech and language difficulties (including reading and writing);

- languages used in the home;

- primary language spoken by the child;

- the family's and other communication partners' perceptions of intelligibility; and

- the teacher's perception of the child's intelligibility and participation in the school setting and how the child's speech compares with that of peers in the classroom.

See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Cultural Responsiveness for guidance on taking a case history with all clients.

Oral Mechanism Examination

The oral mechanism examination evaluates the structure and function of the speech mechanism to assess whether the system is adequate for speech production. This examination typically includes assessment of

- dental occlusion and specific tooth deviations;

- structure of hard and soft palate (clefts, fistulas, bifid uvula); and

- function (strength and range of motion) of the lips, jaw, tongue, and velum.

Hearing Screening

A hearing screening is conducted during the comprehensive speech sound assessment, if one was not completed during the screening.

Hearing screening typically includes

- otoscopic inspection of the ear canal and tympanic membrane;

- pure-tone audiometry; and

- immittance testing to assess middle ear function.

Speech Sound Assessment

The speech sound assessment uses both standardized assessment instruments and other sampling procedures to evaluate production in single words and connected speech.

Single-word testing provides identifiable units of production and allows most consonants in the language to be elicited in a number of phonetic contexts; however, it may or may not accurately reflect production of the same sounds in connected speech.

Connected speech sampling provides information about production of sounds in connected speech using a variety of talking tasks (e.g., storytelling or retelling, describing pictures, normal conversation about a topic of interest) and with a variety of communication partners (e.g., peers, siblings, parents, and clinician).

Assessment of speech includes evaluation of the following:

- Accurate productions

- sounds in various word positions (e.g., initial, within word, and final word position) and in different phonetic contexts;

- sound combinations such as vowel combinations, consonant clusters, and blends; and

- syllable shapes—simple CV to complex CCVCC.

- Speech sound errors

- consistent sound errors;

- error types (e.g., deletions, omissions, substitutions, distortions, additions); and

- error distribution (e.g., position of sound in word).

- Error patterns (i.e., phonological patterns)—systematic sound changes or simplifications that affect a class of sounds (e.g., fricatives), sound combinations (e.g., consonant clusters), or syllable structures (e.g., complex syllables or multisyllabic words).

See Age of Acquisition of English Consonants (Crowe & McLeaod, 2020) [PDF] and ASHA's resource on selected phonological processes (patterns).

Severity Assessment

Severity is a qualitative judgment made by the clinician indicating the impact of the child's speech sound disorder on functional communication. It is typically defined along a continuum from mild to severe or profound. There is no clear consensus regarding the best way to determine severity of a speech sound disorder—rating scales and quantitative measures have been used.

A numerical scale or continuum of disability is often used because it is time-efficient. Prezas and Hodson (2010) use a continuum of severity from mild (omissions are rare; few substitutions) to profound (extensive omissions and many substitutions; extremely limited phonemic and phonotactic repertoires). Distortions and assimilations occur in varying degrees at all levels of the continuum.

A quantitative approach (Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1982a, 1982b) uses the percentage of consonants correct (PCC) to determine severity on a continuum from mild to severe.

To determine PCC, collect and phonetically transcribe a speech sample. Then count the total number of consonants in the sample and the total number of correct consonants. Use the following formula:

PCC = (correct consonants/total consonants) × 100

A PCC of 85–100 is considered mild, whereas a PCC of less than 50 is considered severe. This approach has been modified to include a total of 10 such indices, including percent vowels correct (PVC; Shriberg, Austin, Lewis, McSweeny, & Wilson, 1997).

Intelligibility Assessment

Intelligibility is a perceptual judgment that is based on how much of the child's spontaneous speech the listener understands. Intelligibility can vary along a continuum ranging from intelligible (message is completely understood) to unintelligible (message is not understood; Bernthal et al., 2017). Intelligibility is frequently used when judging the severity of the child's speech problem (Kent, Miolo, & Bloedel, 1994; Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1982b) and can be used to determine the need for intervention.

Intelligibility can vary depending on a number of factors, including

- the number, type, and frequency of speech sound errors (when present);

- the speaker's rate, inflection, stress patterns, pauses, voice quality, loudness, and fluency;

- linguistic factors (e.g., word choice and grammar);

- complexity of utterance (e.g., single words vs. conversational or connected speech);

- the listener's familiarity with the speaker's speech pattern;

- communication environment (e.g., familiar vs. unfamiliar communication partners, one-on-one vs. group conversation);

- communication cues for listener (e.g., nonverbal cues from the speaker, including gestures and facial expressions); and

- signal-to-noise ratio (i.e., amount of background noise).

Rating scales and other estimates that are based on perceptual judgments are commonly used to assess intelligibility. For example, rating scales sometimes use numerical ratings like 1 for totally intelligible and 10 for unintelligible, or they use descriptors like not at all, seldom, sometimes, most of the time, or always to indicated how well speech is understood (Ertmer, 2010).

A number of quantitative measures also have been proposed, including calculating the percentage of words understood in conversational speech (e.g., Flipsen, 2006; Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1980). See also Kent et al. (1994) for a comprehensive review of procedures for assessing intelligibility.

Coplan and Gleason (1988) developed a standardized intelligibility screener using parent estimates of how intelligible their child sounded to others. On the basis of the data, expected intelligibility cutoff values for typically developing children were as follows:

22 months—50%

37 months—75%

47 months—100%

See the Resources section for resources related to assessing intelligibility and life participation in monolingual children who speak English and in monolingual children who speak languages other than English.

Stimulability Testing

Stimulability is the child's ability to accurately imitate a misarticulated sound when the clinician provides a model. There are few standardized procedures for testing stimulability (Glaspey & Stoel-Gammon, 2007; Powell & Miccio, 1996), although some test batteries include stimulability subtests.

Stimulability testing helps determine

- how well the child imitates the sound in one or more contexts (e.g., isolation, syllable, word, phrase);

- the level of cueing necessary to achieve the best production (e.g., auditory model; auditory and visual model; auditory, visual, and verbal model; tactile cues);

- whether the sound is likely to be acquired without intervention; and

- which targets are appropriate for therapy (Tyler & Tolbert, 2002).

Speech Perception Testing

Speech perception is the ability to perceive differences between speech sounds. In children with speech sound disorders, speech perception is the child's ability to perceive the difference between the standard production of a sound and his or her own error production—or to perceive the contrast between two phonetically similar sounds (e.g., r/w, s/ʃ, f/θ).

Speech perception abilities can be tested using the following paradigms:

- Auditory Discrimination—syllable pairs containing a single phoneme contrast are presented, and the child is instructed to say "same" if the paired items sound the same and "different" if they sound different.

- Picture Identification—the child is shown two to four pictures representing words with minimal phonetic differences. The clinician says one of these words, and the child is asked to point to the correct picture.

- Pronunciation Accuracy/Inaccuracy

- Speech production–perception task—using sounds that the child is suspected of having difficulty perceiving, picture targets containing these sounds are used as visual cues. The child is asked to judge whether the speaker says the item correctly (e.g., picture of a ship is shown; speaker says, "ship" or "sip"; Locke, 1980).

- Mispronunciation detection task—using computer-presented picture stimuli and recorded stimulus names (either correct or with a single phoneme error), the child is asked to detect mispronunciations by pointing to a green tick for "correct" or a red cross for "incorrect" (McNeill & Hesketh, 2010).

- Lexical decision/judgment task—using target pictures and single-word recordings, this task assesses the child's ability to identify words that are pronounced correctly or incorrectly. A picture of the target word (e.g., "lake") is shown, along with a recorded word—either "lake" or a word with a contrasting phoneme (e.g., "wake"). The child points to the picture of the target word if it was pronounced correctly or to an "X" if it was pronounced incorrectly (Rvachew, Nowak, & Cloutier, 2004).

Considerations For Assessing Young Children and/or Children Who Are Reluctant or Have Less Intelligible Speech

Young children might not be able to follow directions for standardized tests, might have limited expressive vocabulary, and might produce words that are unintelligible. Other children, regardless of age, may produce less intelligible speech or be reluctant to speak in an assessment setting.

Strategies for collecting an adequate speech sample with these populations include

- obtaining a speech sample during the assessment session using play activities;

- using pictures or toys to elicit a range of consonant sounds;

- involving parents/caregivers in the session to encourage talking;

- asking parents/caregivers to supplement data from the assessment session by recording the child's speech at home during spontaneous conversation; and

- asking parents/caregivers to keep a log of the child's intended words and how these words are pronounced.

Sometimes, the speech sound disorder is so severe that the child's intended message cannot be understood. However, even when a child's speech is unintelligible, it is usually possible to obtain information about his or her speech sound production.

For example:

- A single-word articulation test provides opportunities for production of identifiable units of sound, and these productions can usually be transcribed.

- It may be possible to understand and transcribe a spontaneous speech sample by (a) using a structured situation to provide context when obtaining the sample and (b) annotating the recorded sample by repeating the child's utterances, when possible, to facilitate later transcription.

Considerations For Assessing Bilingual/Multilingual Populations

Assessment of a bilingual individual requires an understanding of both linguistic systems because the sound system of one language can influence the sound system of another language. The assessment process must identify whether differences are truly related to a speech sound disorder or are normal variations of speech caused by the first language.

When assessing a bilingual or multilingual individual, clinicians typically

- gather information, including

- language history and language use to determine which language(s) should be assessed,

- phonemic inventory, phonological structure, and syllable structure of the non-English language, and

- dialect of the individual;

- assess phonological skills in both languages in single words as well as in connected speech;

- account for dialectal differences, when present; and

- identify and assess the child's

- common substitution patterns (those seen in typically developing children),

- uncommon substitution patterns (those often seen in individuals with a speech sound disorder), and

- cross-linguistic effects (the phonological system of one's native language influencing the production of sounds in English, resulting in an accent—that is, phonetic traits from a person's original language (L1) that are carried over to a second language (L2; Fabiano-Smith & Goldstein, 2010).

See phonemic inventories and cultural and linguistic information across languages and ASHA's Practice Portal page on Multilingual Service Delivery in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology. See the Resources section for information related to assessing intelligibility and life participation in monolingual children who speak English and in monolingual children who speak languages other than English.

Phonological Processing Assessment

Phonological processing is the use of the sounds of one's language (i.e., phonemes) to process spoken and written language (Wagner & Torgesen, 1987). The broad category of phonological processing includes phonological awareness, phonological working memory, and phonological retrieval.

All three components of phonological processing (see definitions below) are important for speech production and for the development of spoken and written language skills. Therefore, it is important to assess phonological processing skills and to monitor the spoken and written language development of children with phonological processing difficulties.

- Phonological Awareness is the awareness of the sound structure of a language and the ability to consciously analyze and manipulate this structure via a range of tasks, such as speech sound segmentation and blending at the word, onset-rime, syllable, and phonemic levels.

- Phonological Working Memory involves storing phoneme information in a temporary, short-term memory store (Wagner & Torgesen, 1987). This phonemic information is then readily available for manipulation during phonological awareness tasks. Nonword repetition (e.g., repeat "/pæɡ/") is one example of a phonological working memory task.

- Phonological Retrieval is the ability to retrieve phonological information from long-term memory. It is typically assessed using rapid naming tasks (e.g., rapid naming of objects, colors, letters, or numbers). This ability to retrieve the phonological information of one's language is integral to phonological awareness.

Language Assessments

Language testing is included in a comprehensive speech sound assessment because of the high incidence of co-occurring language problems in children with speech sound disorders (Shriberg & Austin, 1998).

Spoken Language Assessment (Listening and Speaking)

Typically, the assessment of spoken language begins with a screening of expressive and receptive skills; a full battery is performed if indicated by screening results. See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Spoken Language Disorders for more details.

Written Language Assessment (Reading and Writing)

Difficulties with the speech processing system (e.g., listening, discriminating speech sounds, remembering speech sounds, producing speech sounds) can lead to speech production and phonological awareness difficulties. These difficulties can have a negative impact on the development of reading and writing skills (Anthony et al., 2011; Catts, McIlraith, Bridges, & Nielsen, 2017; Leitão & Fletcher, 2004; Lewis et al., 2011).

For typically developing children, speech production and phonological awareness develop in a mutually supportive way (Carroll, Snowling, Stevenson, & Hulme, 2003; National Institute for Literacy, 2009). As children playfully engage in sound play, they eventually learn to segment words into separate sounds and to "map" sounds onto printed letters.

The understanding that sounds are represented by symbolic code (e.g., letters and letter combinations) is essential for reading and spelling. When reading, children have to be able to segment a written word into individual sounds, based on their knowledge of the code and then blend those sounds together to form a word. When spelling, children have to be able to segment a spoken word into individual sounds and then choose the correct code to represent these sounds (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000; Pascoe, Stackhouse, & Wells, 2006).

Components of the written language assessment include the following, depending on the child's age and expected stage of written language development:

- Print Awareness—recognizing that books have a front and back, recognizing that the direction of words is from left to right, and recognizing where words on the page start and stop.

- Alphabet Knowledge—including naming/printing alphabet letters from A to Z.

- Sound–Symbol Correspondence—knowing that letters have sounds and knowing the sounds for corresponding letters and letter combinations.

- Reading Decoding—using sound–symbol knowledge to segment and blend sounds in grade-level words.

- Spelling—using sound–symbol knowledge to spell grade-level words.

- Reading Fluency—reading smoothly without frequent or significant pausing.

- Reading Comprehension—understanding grade-level text, including the ability to make inferences.

See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Written Language Disorders for more details.

See the Treatment section of the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

The broad term "speech sound disorder(s)" is used in this Portal page to refer to functional speech sound disorders, including those related to the motor production of speech sounds (articulation) and those related to the linguistic aspects of speech production (phonological).

It is often difficult to cleanly differentiate between articulation and phonological errors or to differentially diagnose these two separate disorders. Nevertheless, we often talk about articulation error types and phonological error types within the broad diagnostic category of speech sound disorder(s). A single child might show both error types, and those specific errors might need different treatment approaches.

Historically, treatments that focus on motor production of speech sounds are called articulation approaches; treatments that focus on the linguistic aspects of speech production are called phonological/language-based approaches.

Articulation approaches target each sound deviation and are often selected by the clinician when the child's errors are assumed to be motor based; the aim is correct production of the target sound(s).

Phonological/language-based approaches target a group of sounds with similar error patterns, although the actual treatment of exemplars of the error pattern may target individual sounds. Phonological approaches are often selected in an effort to help the child internalize phonological rules and generalize these rules to other sounds within the pattern (e.g., final consonant deletion, cluster reduction).

Articulation and phonological/language-based approaches might both be used in therapy with the same individual at different times or for different reasons.

Both approaches for the treatment of speech sound disorders typically involve the following sequence of steps:

- Establishment—eliciting target sounds and stabilizing production on a voluntary level.

- Generalization—facilitating carry-over of sound productions at increasingly challenging levels (e.g., syllables, words, phrases/sentences, conversational speaking).

- Maintenance—stabilizing target sound production and making it more automatic; encouraging self-monitoring of speech and self-correction of errors.

Target Selection

Approaches for selecting initial therapy targets for children with articulation and/or phonological disorders include the following:

- Developmental—target sounds are selected on the basis of order of acquisition in typically developing children.

- Non-developmental/theoretically motivated, including the following:

- Complexity—focuses on more complex, linguistically marked phonological elements not in the child's phonological system to encourage cascading, generalized learning of sounds (Gierut, 2007; Storkel, 2018).

- Dynamic systems—focuses on teaching and stabilizing simple target phonemes that do not introduce new feature contrasts in the child's phonological system to assist in the acquisition of target sounds and more complex targets and features (Rvachew & Bernhardt, 2010).

- Systemic—focuses on the function of the sound in the child's phonological organization to achieve maximum phonological reorganization with the least amount of intervention. Target selection is based on a distance metric. Targets can be maximally distinct from the child's error in terms of place, voice, and manner and can also be maximally different in terms of manner, place of production, and voicing (Williams, 2003b). See Place, Manner and Voicing Chart for English Consonants (Roth & Worthington, 2018).

- Client-specific—selects targets based on factors such as relevance to the child and his or her family (e.g., sound is in child's name), stimulability, and/or visibility when produced (e.g., /f/ vs. /k/).

- Degree of deviance and impact on intelligibility—selects targets on the basis of errors (e.g., errors of omission; error patterns such as initial consonant deletion) that most effect intelligibility.

See ASHA's Person-Centered Focus on Function: Speech Sound Disorder [PDF] for an example of goal setting consistent with ICF.

Treatment Strategies

In addition to selecting appropriate targets for therapy, SLPs select treatment strategies based on the number of intervention goals to be addressed in each session and the manner in which these goals are implemented. A particular strategy may not be appropriate for all children, and strategies may change throughout the course of intervention as the child's needs change.

"Target attack" strategies include the following:

- Vertical—intense practice on one or two targets until the child reaches a specific criterion level (usually conversational level) before proceeding to the next target or targets (see, e.g., Fey, 1986).

- Horizontal—less intense practice on a few targets; multiple targets are addressed individually or interactively in the same session, thus providing exposure to more aspects of the sounds system (see, e.g., Fey, 1986).

- Cyclical—incorporating elements of both horizontal and vertical structures; the child is provided with practice on a given target or targets for some predetermined period of time before moving on to another target or targets for a predetermined period of time. Practice then cycles through all targets again (see, e.g., Hodson, 2010).

Treatment Options

The following are brief descriptions of both general and specific treatments for children with speech sound disorders. These approaches can be used to treat speech sound problems in a variety of populations. See Speech Characteristics: Selected Populations [PDF] for a brief summary of selected populations and characteristic speech problems.

Treatment selection will depend on a number of factors, including the child's age, the type of speech sound errors, the severity of the disorder, and the degree to which the disorder affects overall intelligibility (Williams, McLeod, & McCauley, 2010). This list is not exhaustive, and inclusion does not imply an endorsement from ASHA.

Contextual Utilization Approaches

Contextual utilization approaches recognize that speech sounds are produced in syllable-based contexts in connected speech and that some (phonemic/phonetic) contexts can facilitate correct production of a particular sound.

Contextual utilization approaches may be helpful for children who use a sound inconsistently and need a method to facilitate consistent production of that sound in other contexts. Instruction for a particular sound is initiated in the syllable context(s) where the sound can be produced correctly (McDonald, 1974). The syllable is used as the building block for practice at more complex levels.

For example, production of a "t" may be facilitated in the context of a high front vowel, as in "tea" (Bernthal et al., 2017). Facilitative contexts or "likely best bets" for production can be identified for voiced, velar, alveolar, and nasal consonants. For example, a "best bet" for nasal consonants is before a low vowel, as in "mad" (Bleile, 2002).

Phonological Contrast Approaches

Phonological contrast approaches are frequently used to address phonological error patterns. They focus on improving phonemic contrasts in the child's speech by emphasizing sound contrasts necessary to differentiate one word from another. Contrast approaches use contrasting word pairs as targets instead of individual sounds.

There are four different contrastive approaches—minimal oppositions, maximal oppositions, treatment of the empty set, and multiple oppositions.

- Minimal Oppositions (also known as "minimal pairs" therapy)—uses pairs of words that differ by only one phoneme or single feature signaling a change in meaning. Minimal pairs are used to help establish contrasts not present in the child's phonological system (e.g., "door" vs. "sore," "pot" vs. "spot," "key" vs. "tea"; Blache, Parsons, & Humphreys, 1981; Weiner, 1981).

- Maximal Oppositions—uses pairs of words containing a contrastive sound that is maximally distinct and varies on multiple dimensions (e.g., voice, place, and manner) to teach an unknown sound. For example, "mall" and "call" are maximal pairs because /m/ and /k/ vary on more than one dimension—/m/ is a bilabial voiced nasal, whereas /k/ is a velar voiceless stop (Gierut, 1989, 1990, 1992). See Place, Manner and Voicing Chart for English Consonants (Roth & Worthington, 2018).

- Treatment of the Empty Set—similar to the maximal oppositions approach but uses pairs of words containing two maximally opposing sounds (e.g., /r/ and /d/) that are unknown to the child (e.g., "row" vs. "doe" or "ray" vs. "day"; Gierut, 1992).

- Multiple Oppositions—a variation of the minimal oppositions approach but uses pairs of words contrasting a child's error sound with three or four strategically selected sounds that reflect both maximal classification and maximal distinction (e.g., "door," "four," "chore," and "store," to reduce backing of /d/ to /g/; Williams, 2000a, 2000b).

Complexity Approach

The complexity approach is a speech production approach based on data supporting the view that the use of more complex linguistic stimuli helps promote generalization to untreated but related targets.

The complexity approach grew primarily from the maximal oppositions approach. However, it differs from the maximal oppositions approach in a number of ways. Rather than selecting targets on the basis of features such as voice, place, and manner, the complexity of targets is determined in other ways. These include hierarchies of complexity (e.g., clusters, fricatives, and affricates are more complex than other sound classes) and stimulability (i.e., sounds with the lowest levels of stimulability are most complex). In addition, although the maximal oppositions approach trains targets in contrasting word pairs, the complexity approach does not. See Baker and Williams (2010) and Peña-Brooks and Hegde (2015) for detailed descriptions of the complexity approach.

Core Vocabulary Approach

A core vocabulary approach focuses on whole-word production and is used for children with inconsistent speech sound production who may be resistant to more traditional therapy approaches.

Words selected for practice are those used frequently in the child's functional communication. A list of frequently used words is developed (e.g., based on observation, parent report, and/or teacher report), and a number of words from this list are selected each week for treatment. The child is taught his or her "best" word production, and the words are practiced until consistently produced (Dodd, Holm, Crosbie, & McIntosh, 2006).

Cycles Approach

The cycles approach targets phonological pattern errors and is designed for children with highly unintelligible speech who have extensive omissions, some substitutions, and a restricted use of consonants.

Treatment is scheduled in cycles ranging from 5 to 16 weeks. During each cycle, one or more phonological patterns are targeted. After each cycle has been completed, another cycle begins, targeting one or more different phonological patterns. Recycling of phonological patterns continues until the targeted patterns are present in the child's spontaneous speech (Hodson, 2010; Prezas & Hodson, 2010).

The goal is to approximate the gradual typical phonological development process. There is no predetermined level of mastery of phonemes or phoneme patterns within each cycle; cycles are used to stimulate the emergence of a specific sound or pattern—not to produce mastery of it.

Distinctive Feature Therapy

Distinctive feature therapy focuses on elements of phonemes that are lacking in a child's repertoire (e.g., frication, nasality, voicing, and place of articulation) and is typically used for children who primarily substitute one sound for another. See Place, Manner and Voicing Chart for English Consonants (Roth & Worthington, 2018).

Distinctive feature therapy uses targets (e.g., minimal pairs) that compare the phonetic elements/features of the target sound with those of its substitution or some other sound contrast. Patterns of features can be identified and targeted; producing one target sound often generalizes to other sounds that share the targeted feature (Blache & Parsons, 1980; Blache et al., 1981; Elbert & McReynolds, 1978; McReynolds & Bennett, 1972; Ruder & Bunce, 1981).

Metaphon Therapy

Metaphon therapy is designed to teach metaphonological awareness—that is, the awareness of the phonological structure of language. This approach assumes that children with phonological disorders have failed to acquire the rules of the phonological system.

The focus is on sound properties that need to be contrasted. For example, for problems with voicing, the concept of "noisy" (voiced) versus "quiet" (voiceless) is taught. Targets typically include processes that affect intelligibility, can be imitated, or are not seen in typically developing children of the same age (Dean, Howell, Waters, & Reid, 1995; Howell & Dean, 1994).

Naturalistic Speech Intelligibility Intervention

Naturalist speech intelligibility intervention addresses the targeted sound in naturalistic activities that provide the child with frequent opportunities for the sound to occur. For example, using a McDonald's menu, signs at the grocery store, or favorite books, the child can be asked questions about words that contain the targeted sound(s). The child's error productions are recast without the use of imitative prompts or direct motor training. This approach is used with children who are able to use the recasts effectively (Camarata, 2010).

Nonspeech Oral–Motor Therapy

Nonspeech oral–motor therapy involves the use of oral-motor training prior to teaching sounds or as a supplement to speech sound instruction. The rationale behind this approach is that (a) immature or deficient oral-motor control or strength may be causing poor articulation and (b) it is necessary to teach control of the articulators before working on correct production of sounds. Consult systematic reviews of this treatment to help guide clinical decision making (see, e.g., Lee & Gibbon, 2015 [PDF]; McCauley, Strand, Lof, Schooling, & Frymark, 2009). See also the Treatment section of the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map filtered for Oral–Motor Exercises.

Speech Sound Perception Training

Speech sound perception training is used to help a child acquire a stable perceptual representation for the target phoneme or phonological structure. The goal is to ensure that the child is attending to the appropriate acoustic cues and weighting them according to a language-specific strategy (i.e., one that ensures reliable perception of the target in a variety of listening contexts).

Recommended procedures include (a) auditory bombardment in which many and varied target exemplars are presented to the child, sometimes in a meaningful context such as a story and often with amplification, and (b) identification tasks in which the child identifies correct and incorrect versions of the target (e.g., "rat" is a correct exemplar of the word corresponding to a rodent, whereas "wat" is not).

Tasks typically progress from the child judging speech produced by others to the child judging the accuracy of his or her own speech. Speech sound perception training is often used before and/or in conjunction with speech production training approaches. See Rvachew, 1994; Rvachew et al., 2004; Rvachew, Rafaat, & Martin, 1999; Wolfe, Presley, & Mesaris, 2003.

Traditionally, the speech stimuli used in these tasks are presented via live voice by the SLP. More recently, computer technology has been used—an advantage of this approach is that it allows for the presentation of more varied stimuli representing, for example, multiple voices and a range of error types.

Treatment Techniques and Technologies

Techniques used in therapy to increase awareness of the target sound and/or provide feedback about placement and movement of the articulators include the following:

- Using a mirror for visual feedback of place and movement of articulators

- Using gestural cueing for place or manner of production (e.g., using a long, sweeping hand gesture for fricatives vs. a short, "chopping" gesture for stops)

- Using ultrasound imaging (placement of an ultrasound transducer under the chin) as a biofeedback technique to visualize tongue position and configuration (Adler-Bock, Bernhardt, Gick, & Bacsfalvi, 2007; Lee, Wrench, & Sancibrian, 2015; Preston, Brick, & Landi, 2013; Preston et al., 2014)

- Using palatography (various coloring agents or a palatal device with electrodes) to record and visualize contact of the tongue on the palate while the child makes different speech sounds (Dagenais, 1995; Gibbon, Stewart, Hardcastle, & Crampin, 1999; Hitchcock, McAllister Byun, Swartz, & Lazarus, 2017)

- Amplifying target sounds to improve attention, reduce distractibility, and increase sound awareness and discrimination—for example, auditory bombardment with low-level amplification is used with the cycles approach at the beginning and end of each session to help children perceive differences between errors and target sounds (Hodson, 2010)

- Providing spectral biofeedback through a visual representation of the acoustic signal of speech (McAllister Byun & Hitchcock, 2012)

- Providing tactile biofeedback using tools, devices, or substances placed within the mouth (e.g., tongue depressors, peanut butter) to provide feedback on correct tongue placement and coordination (Altshuler, 1961; Leonti, Blakeley, & Louis, 1975; Shriberg, 1980)

Considerations for Treating Bilingual/Multilingual Populations

When treating a bilingual or multilingual individual with a speech sound disorder, the clinician is working with two or more different sound systems. Although there may be some overlap in the phonemic inventories of each language, there will be some sounds unique to each language and different phonemic rules for each language.

One linguistic sound system may influence production of the other sound system. It is the role of the SLP to determine whether any observed differences are due to a true communication disorder or whether these differences represent variations of speech associated with another language that a child speaks.

Strategies used when designing a treatment protocol include

- determining whether to use a bilingual or cross-linguistic approach (see ASHA's Practice Portal page on Multilingual Service Delivery in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology);

- determining the language in which to provide services, on the basis of factors such as language history, language use, and communicative needs;

- identifying alternative means of providing accurate models for target phonemes that are unique to the child's language, when the clinician is unable to do so; and

- noting if success generalizes across languages throughout the treatment process (Goldstein & Fabiano, 2007).

Considerations for Treatment in Schools

Criteria for determining eligibility for services in a school setting are detailed in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEA). In accordance with these criteria, the SLP needs to determine

- if the child has a speech sound disorder;

- if there is an adverse effect on educational performance resulting from the disability; and

- if specially designed instruction and/or related services and supports are needed to help the student make progress in the general education curriculum.

Examples of the adverse effect on educational performance include the following:

- The speech sound disorder affects the child's ability or willingness to communicate in the classroom (e.g., when responding to teachers' questions; during classroom discussions or oral presentations) and in social settings with peers (e.g., interactions during lunch, recess, physical education, and extracurricular activities).

- The speech sound disorder signals problems with phonological skills that affect spelling, reading, and writing. For example, the way a child spells a word reflects the errors made when the word is spoken. See ASHA's resource language in brief and ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Spoken Language Disorders and Written Language Disorders for more information about the relationship between spoken and written language

Eligibility for speech-language pathology services is documented in the child's individualized education program, and the child's goals and the dismissal process are explained to parents and teachers. For more information about eligibility for services in the schools, see ASHA's resources on eligibility and dismissal in schools, IDEA Part B Issue Brief: Individualized Education Programs and Eligibility for Services, and 2011 IDEA Part C Final Regulations.

If a child is not eligible for services under IDEA, they may still be eligible to receive services under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504. 29 U.S.C. § 701 (1973). See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Documentation in Schools for more information about Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

Dismissal from speech-language pathology services occurs once eligibility criteria are no longer met—that is, when the child's communication problem no longer adversely affects academic achievement and functional performance.

Children With Persisting Speech Difficulties

Speech difficulties sometimes persist throughout the school years and into adulthood. Pascoe et al. (2006) define persisting speech difficulties as "difficulties in the normal development of speech that do not resolve as the child matures or even after they receive specific help for these problems" (p. 2). The population of children with persistent speech difficulties is heterogeneous, varying in etiology, severity, and nature of speech difficulties (Dodd, 2005; Shriberg et al., 2010; Stackhouse, 2006; Wren, Roulstone, & Miller, 2012).

A child with persisting speech difficulties (functional speech sound disorders) may be at risk for

- difficulty communicating effectively when speaking;

- difficulty acquiring reading and writing skills; and

- psychosocial problems (e.g., low self-esteem, increased risk of bullying; see, e.g., McCormack, McAllister, McLeod, & Harrison, 2012).

Intervention approaches vary and may depend on the child's area(s) of difficulty (e.g., spoken language, written language, and/or psychosocial issues).

In designing an effective treatment protocol, the SLP considers

- teaching and encouraging the use of self-monitoring strategies to facilitate consistent use of learned skills;

- collaborating with teachers and other school personnel to support the child and to facilitate his or her access to the academic curriculum; and

- managing psychosocial factors, including self-esteem issues and bullying (Pascoe et al., 2006).

Transition Planning

Children with persisting speech difficulties may continue to have problems with oral communication, reading and writing, and social aspects of life as they transition to post-secondary education and vocational settings (see, e.g., Carrigg, Baker, Parry, & Ballard, 2015). The potential impact of persisting speech difficulties highlights the need for continued support to facilitate a successful transition to young adulthood. These supports include the following:

- Transition Planning—the development of a formal transition plan in middle or high school that includes discussion of the need for continued therapy, if appropriate, and supports that might be needed in postsecondary educational and/or vocational settings (IDEA, 2004).

- Disability Support Services—individualized support for postsecondary students that may include extended time for tests, accommodations for oral speaking assignments, the use of assistive technology (e.g., to help with reading and writing tasks), and the use of methods and devices to augment oral communication, if necessary.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 provide protections for students with disabilities who are transitioning to postsecondary education. The protections provided by these acts (a) ensure that programs are accessible to these students and (b) provide aids and services necessary for effective communication (U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2011).

For more information about transition planning, see ASHA's resource on Postsecondary Transition Planning.

Service Delivery

See the Service Delivery section of the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

In addition to determining the type of speech and language treatment that is optimal for children with speech sound disorders, SLPs consider the following other service delivery variables that may have an impact on treatment outcomes:

- Dosage—the frequency, intensity, and duration of service

- Format—whether a person is seen for treatment one-on-one (i.e., individual) or as part of a group

- Provider—the person administering the treatment (e.g., SLP, trained volunteer, caregiver)

- Setting—the location of treatment (e.g. home, community-based, school [pull-out or within the classroom])

- Timing—when intervention occurs relative to the diagnosis.

Technology can be incorporated into the delivery of services for speech sound disorders, including the use of telepractice as a format for delivering face-to-face services remotely. See ASHA's Practice Portal page on Telepractice.

The combination of service delivery factors is important to consider so that children receive optimal intervention intensity to ensure that efficient, effective change occurs (Baker, 2012; Williams, 2012).

ASHA Resources

- Consumer Information: Speech Sound Disorders

- Focusing Care on Individuals and Their Care Partners

- Interprofessional Education/Interprofessional Practice (IPE/IPP)

- Let's Talk: For People With Special Communication Needs

- Person-Centered Focus on Function: Speech Sound Disorder [PDF]

- Phonemic Inventories and Cultural and Linguistic Information Across Languages

- Postsecondary Transition Planning

- Selected Phonological Processes (Patterns)

Other Resources

- Age of Acquisition of English Consonants (Crowe & McLeod, 2020) [PDF]

- American Cleft Palate–Craniofacial Association

- English Consonant and Vowel Charts (University of Arizona)

- Everyone Has an Accent

- Free Resources for the Multiple Oppositions approach - Adventures in Speech Pathology

- Multilingual Children's Speech: Overview

- Multilingual Children's Speech: Intelligibility in Context Scale

- Multilingual Children's Speech: Speech Participation and Activity Assessment of Children (SPAA-C)

- Phonetics: The Sounds of American English (University of Iowa)

- Phonological and Phonemic Awareness

- Place, Manner and Voicing Chart for English Consonants (Roth & Worthington, 2018)

- RCSLT: New Long COVID Guidance and Patient Handbook

- The Development of Phonological Skills (WETA Educational Website)

- The Speech Accent Archive (George Mason University)

Adler-Bock, M., Bernhardt, B. M., Gick, B., & Bacsfalvi, P. (2007). The use of ultrasound in remediation of North American English /r/ in 2 adolescents. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 128–139.

Altshuler, M. W. (1961). A therapeutic oral device for lateral emission. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 26, 179–181.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016a). Code of ethics [Ethics]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (20016b). Scope of practice in speech-language-pathology [Scope of Practice]. Available from www.asha.org/policy/

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, P.L. 101-336, 42 U.S.C. §§ 12101 et seq.

Anthony, J. L., Aghara, R. G., Dunkelberger, M. J., Anthony, T. I., Williams, J. M., & Zhang, Z. (2011). What factors place children with speech sound disorders at risk for reading problems? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 146–160.

Baker, E. (2012). Optimal intervention intensity. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14, 401–409.

Baker, E., & Williams, A. L. (2010). Complexity approaches to intervention. In S. F. Warren & M. E. Fey (Series Eds.). & A. L. Williams, S. McLeod, & R. J. McCauley (Volume Eds.), Intervention for speech sound disorders in children (pp. 95–115). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Bernthal, J., Bankson, N. W., & Flipsen, P., Jr. (2017). Articulation and phonological disorders: Speech sound disorders in children. New York, NY: Pearson.

Blache, S., & Parsons, C. (1980). A linguistic approach to distinctive feature training. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 11, 203–207.

Blache, S. E., Parsons, C. L., & Humphreys, J. M. (1981). A minimal-word-pair model for teaching the linguistic significant difference of distinctive feature properties. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46, 291–296.

Black, L. I., Vahratian, A., & Hoffman, H. J. (2015). Communication disorders and use of intervention services among children aged 3–17 years; United States, 2012 (NHS Data Brief No. 205). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Bleile, K. (2002). Evaluating articulation and phonological disorders when the clock is running. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11, 243–249.

Byers Brown, B., Bendersky, M., & Chapman, T. (1986). The early utterances of preterm infants. British Journal of Communication Disorders, 21, 307–320.

Camarata, S. (2010). Naturalistic intervention for speech intelligibility and speech accuracy. In A. L. Williams, S. McLeod, & R. J. McCauley (Eds.), Interventions for speech sound disorders in children (pp. 381–406). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Campbell, T. F., Dollaghan, C. A., Rockette, H. E., Paradise, J. L., Feldman, H. M., Shriberg, L. D., . . . Kurs-Lasky, M. (2003). Risk factors for speech delay of unknown origin in 3-year-old children. Child Development, 74, 346–357.

Carrigg, B., Baker, E., Parry, L., & Ballard, K. J. (2015). Persistent speech sound disorder in a 22-year-old male: Communication, educational, socio-emotional, and vocational outcomes. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 16, 37–49.

Carroll, J. M., Snowling, M. J., Stevenson, J., & Hulme, C. (2003). The development of phonological awareness in preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 39, 913–923.

Catts, H. W., McIlraith, A., Bridges, M. S., & Nielsen, D. C. (2017). Viewing a phonological deficit within a multifactorial model of dyslexia. Reading and Writing, 30, 613–629.

Coplan, J., & Gleason, J. R. (1988). Unclear speech: Recognition and significance of unintelligible speech in preschool children. Pediatrics, 82, 447–452.

Crowe, K., & McLeod, S. (2020). Children’s English consonant acquisition in the United States: A review. American Journal of Speech-Language

Pathology, 29(4), 2155-2169. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00168.

Dagenais, P. A. (1995). Electropalatography in the treatment of articulation/phonological disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 28, 303–329.

Dean, E., Howell, J., Waters, D., & Reid, J. (1995). Metaphon: A metalinguistic approach to the treatment of phonological disorder in children. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 9, 1–19.

Dodd, B. (2005). Differential diagnosis and treatment of children with speech disorder. London, England: Whurr.

Dodd, B., Holm, A., Crosbie, S., & McIntosh, B. (2006). A core vocabulary approach for management of inconsistent speech disorder. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 8, 220–230.

Eadie, P., Morgan, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Eecen, K. T., Wake, M., & Reilly, S. (2015). Speech sound disorder at 4 years: Prevalence, comorbidities, and predictors in a community cohort of children. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 57, 578–584.

Elbert, M., & McReynolds, L. V. (1978). An experimental analysis of misarticulating children's generalization. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 21, 136–149.

Ertmer, D. J. (2010). Relationship between speech intelligibility and word articulation scores in children with hearing loss. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 1075–1086.

Everhart, R. (1960). Literature survey of growth and developmental factors in articulation maturation. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 25, 59–69.

Fabiano-Smith, L., & Goldstein, B. A. (2010). Phonological acquisition in bilingual Spanish–English speaking children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 160–178.

Felsenfeld, S., McGue, M., & Broen, P. A. (1995). Familial aggregation of phonological disorders: Results from a 28-year follow-up. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 38, 1091–1107.

Fey, M. (1986). Language intervention with young children. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Flipsen, P. (2006). Measuring the intelligibility of conversational speech in children. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 20, 202–312.

Flipsen, P. (2015). Emergence and prevalence of persistent and residual speech errors. Seminars in Speech Language, 36, 217–223.

Fox, A. V., Dodd, B., & Howard, D. (2002). Risk factors for speech disorders in children. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 37, 117–132.

Gibbon, F., Stewart, F., Hardcastle, W. J., & Crampin, L. (1999). Widening access to electropalatography for children with persistent sound system disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 8, 319–333.

Gierut, J. A. (1989). Maximal opposition approach to phonological treatment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 54, 9–19.

Gierut, J. A. (1990). Differential learning of phonological oppositions. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 33, 540–549.

Gierut, J. A. (1992). The conditions and course of clinically induced phonological change. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35, 1049–1063.

Gierut, J. A. (2007). Phonological complexity and language learnability. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 6–17.

Glaspey, A. M., & Stoel-Gammon, C. (2007). A dynamic approach to phonological assessment. Advances in Speech-Language Pathology, 9, 286–296.

Goldstein, B. A., & Fabiano, L. (2007, February 13). Assessment and intervention for bilingual children with phonological disorders. The ASHA Leader, 12, 6–7, 26–27, 31.

Grunwell, P. (1987). Clinical phonology (2nd ed.). London, England: Chapman and Hall.

Hitchcock, E. R., McAllister Byun, T., Swartz, M., & Lazarus, R. (2017). Efficacy of electropalatography for treating misarticulations of /r/. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26, 1141–1158.

Hodson, B. (2010). Evaluating and enhancing children's phonological systems: Research and theory to practice. Wichita, KS: PhonoComp.

Howell, J., & Dean, E. (1994). Treating phonological disorders in children: Metaphon—Theory to practice (2nd ed.). London, England: Whurr.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, P. L. 108-446, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1400 et seq. Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov/

Kent, R. D., Miolo, G., & Bloedel, S. (1994). The intelligibility of children's speech: A review of evaluation procedures. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 3, 81–95.

Law, J., Boyle, J., Harris, F., Harkness, A., & Nye, C. (2000). Prevalence and natural history of primary speech and language delay: Findings from a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 35, 165–188.

Lee, A. S. Y., & Gibbon, F. E. (2015). Non-speech oral motor treatment for children with developmental speech sound disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015 (3), 1–42.

Lee, S. A. S., Wrench, A., & Sancibrian, S. (2015). How to get started with ultrasound technology for treatment of speech sound disorders. Perspectives on Speech Science and Orofacial Disorders, 25, 66–80.

Leitão, S., & Fletcher, J. (2004). Literacy outcomes for students with speech impairment: Long-term follow-up. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 39, 245–256.

Leonti, S., Blakeley, R., & Louis, H. (1975, November). Spontaneous correction of resistant /ɚ/ and /r/ using an oral prosthesis. Paper presented at the annual convention of the American Speech and Hearing Association, Washington, DC.

Lewis, B. A., Avrich, A. A., Freebairn, L. A., Hansen, A. J., Sucheston, L. E., Kuo, I., . . . Stein, C. M. (2011). Literacy outcomes of children with early childhood speech sound disorders: Impact of endophenotypes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54, 1628–1643.

Locke, J. (1980). The inference of speech perception in the phonologically disordered child. Part I: A rationale, some criteria, the conventional tests. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 45, 431–444.

McAllister Byun, T., & Hitchcock, E. R. (2012). Investigating the use of traditional and spectral biofeedback approaches to intervention for /r/ misarticulation. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21, 207–221.

McCauley, R. J., Strand, E., Lof, G. L., Schooling, T., & Frymark, T. (2009). Evidence-based systematic review: Effects of nonspeech oral motor exercises on speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18, 343–360.

McCormack, J., McAllister, L., McLeod, S., & Harrison, L. (2012). Knowing, having, doing: The battles of childhood speech impairment. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 28, 141–157.

McDonald, E. T. (1974).Articulation testing and treatment: A sensory motor approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Stanwix House.

McLeod, S., & Crowe, K. (2018). Children's consonant acquisition in 27 languages: A cross-linguistic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27, 1546–1571.

McLeod, S., Verdon, S., & The International Expert Panel on Multilingual Children's Speech. (2017). Tutorial: Speech assessment for multilingual children who do not speak the same language(s) as the speech-language pathologist. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26, 691–708.

McNeill, B. C., & Hesketh, A. (2010). Developmental complexity of the stimuli included in mispronunciation detection tasks. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 45, 72–82.

McReynolds, L. V., & Bennett, S. (1972). Distinctive feature generalization in articulation training. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 37, 462–470.

Morley, D. (1952). A ten-year survey of speech disorders among university students. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 17, 25–31.

National Institute for Literacy. (2009). Developing early literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel. A scientific synthesis of early literacy development and implications for intervention. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction [Report of the National Reading Panel]. Washington, DC: Author.

Overby, M.S., Trainin, G., Smit, A. B., Bernthal, J. E., & Nelson, R. (2012). Preliteracy speech sound production skill and later literacy outcomes: A study using the Templin Archive. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43, 97–115.

Pascoe, M., Stackhouse, J., & Wells, B. (2006). Persisting speech difficulties in children: Children's speech and literacy difficulties, Book 3. West Sussex, England: Whurr.

Peña-Brooks, A., & Hegde, M. N. (2015). Assessment and treatment of articulation and phonological disorders in children. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Peterson, R. L., Pennington, B. F., Shriberg, L. D., & Boada, R. (2009). What influences literacy outcome in children with speech sound disorder? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 1175-1188.

Powell, T. W., & Miccio, A. W. (1996). Stimulability: A useful clinical tool. Journal of Communication Disorders, 29, 237–253.

Preston, J. L., Brick, N., & Landi, N. (2013). Ultrasound biofeedback treatment for persisting childhood apraxia of speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 22, 627–643.

Preston, J. L., McCabe, P., Rivera-Campos, A., Whittle, J. L., Landry, E., & Maas, E. (2014). Ultrasound visual feedback treatment and practice variability for residual speech sound errors. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57, 2102–2115.

Prezas, R. F., & Hodson, B. W. (2010). The cycles phonological remediation approach. In A. L. Williams, S. McLeod, & R. J. McCauley (Eds.), Interventions for speech sound disorders in children (pp. 137–158). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, P.L. No. 93-112, 29 U.S.C. § 794.

Roth, F. P., & Worthington, C. K. (2018). Treatment resource manual for speech-language pathology. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Ruder, K. F., & Bunce, B. H. (1981). Articulation therapy using distinctive feature analysis to structure the training program: Two case studies. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 46, 59–65.

Rvachew, S. (1994). Speech perception training can facilitate sound production learning. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 37, 347–357.

Rvachew, S., & Bernhardt, B. M. (2010). Clinical implications of dynamic systems theory for phonological development. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19, 34–50.