Tinnitus Evaluation and Management Considerations for Persons with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

April 2009

Paula J. Myers, PhD, CCC-A; James A. Henry, PhD, CCC-A; Tara L. Zaugg, AuD; Caroline J. Kendall, PhD

The leading causes of traumatic brain injury (TBI) in civilians are motor vehicle accidents, falls, and assaults. Blasts are the leading cause of TBI for active-duty service members. The intensified use of explosive devices and mines in warfare and noise from weapons have resulted in auditory dysfunction, tinnitus, TBI, mental health conditions, and pain complaints among members of the military. Symptoms of mild TBI or concussion frequently include tinnitus, which can occur not only as a direct consequence of the injury causing TBI but also as a side effect of medications commonly used to treat cognitive, emotional, and pain problems associated with TBI. The unique occurrence and strong associations between the physical, cognitive, behavioral, and emotional sequelae involved with TBI require audiologists to work as a team with several services.

Mild TBI, particularly for those with closed head injuries, may not be immediately obvious. Audiologists must be prepared to identify those at risk for mild TBI or mental health problems, justify the need for screening and/or clinical referral for further evaluation of TBI and/or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and adapt audiologic clinical tinnitus assessment and management practices to this population.

While the nature and outcomes of brain injuries resulting from blast exposure are not yet fully understood, it is known that TBI causes both acute and delayed symptoms. Each requires prompt identification and multidisciplinary assessment and management. Mild TBI can cause cognitive deficits in speed of information processing, attention, and memory in the immediate postinjury period. Good recovery of postconcussive deficits can be expected over time, usually within a few months for most patients with mild TBI, although some patients may have symptoms for years or develop postconcussion syndrome. Repeated mild TBI occurring over months or years can result in additive neurological deficits.

Often the symptoms of mild TBI are mistaken for signs of PTSD. The problematic overlap and/or associations of mild TBI, PTSD, and depression symptoms are seen in TBI centers. The invisibility of closed head injury, hearing loss, and tinnitus heighten the importance of screening for TBI, PTSD, depression, hearing impairment, and tinnitus in those service members exposed to blast injury.

Improved awareness among audiologists regarding the possibility of mild TBI, pain, and mental health problems in returning soldiers can enhance understanding and empathy for patients and justify the need for screening and/or clinical referral for further evaluation and treatment of TBI, PTSD, and other mental health problems. Displaying posters and handouts on TBI, PTSD, and signs of depression in your clinic can help increase awareness about the conditions and can be a helpful source of information. The following Web sites contain screening information for TBI, PTSD, and other mental health conditions:

For screening and other information on TBI

- Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center

- CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control

- NINDS Traumatic Brain Injury Information Page

For screening and other information on PTSD and related mental health conditions

Progressive Audiologic Tinnitus Management (PATM)

We have described audiologic tinnitus management (ATM) previously (Henry, Zaugg, & Schechter, 2005a, 2005b). The ATM method provided specific guidelines for audiologists to implement a well-defined program of tinnitus management. Our subsequent tinnitus clinical research pointed to the need to provide tinnitus clinical services in a hierarchical manner, that is, to provide services only to the degree necessary to meet patients' individual needs. In addition, we saw a need to make numerous changes to the ATM assessment and intervention methodologies to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the clinical protocol. ATM therefore was completely revamped, resulting in a five-level hierarchical program of tinnitus management that we refer to as progressive audiologic tinnitus management (PATM).

The primary objectives of PATM are to provide the following services to patients who complain of tinnitus: (a) education to facilitate the acquisition of tinnitus self-management skills; (b) a progressive program of assessment and intervention that addresses each patient's individual needs; and (c) ensuring that patients are referred appropriately for medical and mental health services if needed. The management program is goal-oriented with a focus on individualized management, patient and family education, counseling, and support.

PATM uses therapeutic sound as the primary intervention modality, and it is distinguished from other sound-based methods (neuromonics tinnitus treatment, tinnitus masking, and tinnitus retraining therapy) in that the sound-management protocol is adaptive to address patients' unique needs. The specific use of therapeutic sound with PATM can be (a) similar to any of these other methods, (b) a combination of methods, or (c) an altogether different approach to using sound. Therapeutic sound can be used in a variety of ways with PATM, which is necessary because patients encounter different situations that differentially affect how they react to their tinnitus. The use of sound must vary accordingly to appropriately manage each of these situations. These situations also change over time, and the use of sound likewise must adapt to these changes.

The focus of patient education is to provide patients with the knowledge and skills to use sound in adaptive ways to manage their tinnitus in any life situation disrupted by tinnitus. This is accomplished by helping patients develop and implement custom sound-based management plans to address their unique needs. Development of these action plans may be facilitated by the clinician, but the ultimate goal is that patients learn how to devise and implement the plans on their own.

This article provides a brief overview of the PATM method. A Clinician Guidelines Handbook and an online training course (consisting of 19 comprehensive Web modules of training) have been developed to provide detailed clinical education, guides, and tools to conduct PATM (Henry, Zaugg, Myers, & Schecter, 2008c). These materials were developed in conjunction with a randomized clinical trial unded by the VA Rehabilitation Research and Development (RR&D) Service. The materials currently are being edited and reviewed for distribution to all VA medical centers-for utilization primarily by audiologists but also by other clinicians. Although this method has been developed and evaluated for veterans with tinnitus, PATM protocols can be applied to any adult with problematic tinnitus. Although not tested with children, the method is adaptable to that population.

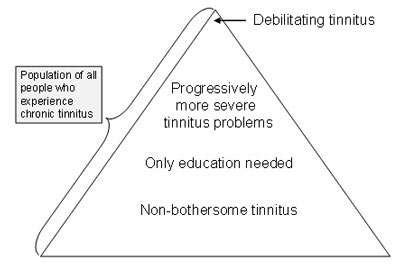

The Tinnitus Pyramid illustrated in Figure 1 is a way of visualizing how people who experience chronic tinnitus are affected differently. The base of the pyramid reveals that most persons who experience tinnitus are not bothered by it or only require some rudimentary information about tinnitus. Epidemiological studies generally reveal that about 80% of people who experience tinnitus are not particularly bothered by it. The remaining 20% are bothered, but to different degrees-as depicted by people with "progressively more severe tinnitus problems" toward the top of the pyramid. The tip of the pyramid contains the relatively few patients who have the most severe tinnitus condition, that is, those who are debilitated by their tinnitus. The Tinnitus Pyramid highlights that patients who complain of tinnitus have very different needs, ranging from the provision of simple information to long-term individualized therapy. This range of needs is what necessitates a progressive management approach.

Figure 1. Tinnitus Pyramid.

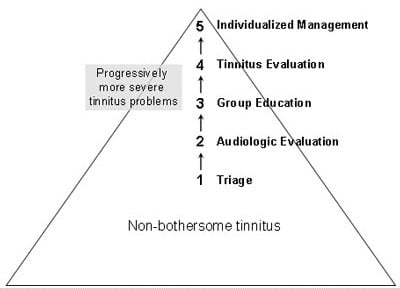

The overall goal of PATM's hierarchical approach is to minimize the impact of tinnitus on patients' lives as efficiently as possible. Because the impact of tinnitus varies widely for these patients, their management needs vary accordingly. PATM provides a structure to clinically manage patients to only the degree necessary. Very few patients require all five levels of procedures. The five levels of PATM superimposed on the Tinnitus Pyramid (see Figure 2) are as follows:

- Level 1 is for referring patients at the initial point of contact-usually by nonaudiologist clinicians.

- Level 2 is the audiologic evaluation with screening for tinnitus clinical significance.

- Level 3 is the provision of structured group educational counseling.

- Level 4 is the comprehensive tinnitus evaluation.

- Level 5 is individualized management for longer-term intervention.

Figure 2. Progressive Audiologic Tinnitus Management (PATM) hierarchical levels.

Multidisciplinary Approach

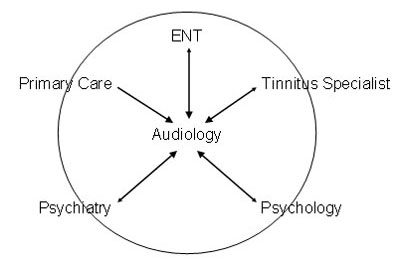

Because tinnitus can affect many aspects of health, a team approach to tinnitus management is the ideal. It is important that patients are referred appropriately to other health care professionals-usually to otolaryngology, psychology, and/or psychiatry as warranted. Whenever possible, mental health professionals should have expertise in the management of tinnitus, or at least be familiar with the nature of tinnitus within the context of coexistent psychological problems.

Management of tinnitus should be coordinated primarily by audiologists. Unless there is a medical or psychiatric emergency, all patients who complain of tinnitus should be referred to an audiologist for a Level 2 Audiologic Evaluation. Audiologists also should refer patients out to other clinics as necessary, as highlighted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Referral options for persons with tinnitus.

Both TBI and tinnitus often are associated with mental health disorders, including PTSD, depression, and anxiety. If left untreated, these mental health conditions can impede any rehabilitation efforts, including the clinical management of tinnitus. Failure to properly refer patients for possible PTSD, depression, and/or chronic anxiety reduces the likelihood of achieving the desired outcomes from tinnitus intervention.

Sleep disturbance is frequently reported by patients with TBI and/or tinnitus. Tinnitus patients who report sleep problems also tend to have the most severe tinnitus. PATM provides sound-based strategies that can help patients improve their sleep without the use of medications or special procedures. If these strategies are unsuccessful, then sleep problems may be mitigated by proper treatment from a physician or mental health professional.

Mild TBI, particularly for patients with closed head injuries, may not be immediately obvious. Dizziness, loss of balance, hearing complaints, tinnitus, and sensitivity to sound are among several potential symptoms of postconcussion syndrome, but they also are symptoms of peripheral, vestibular, and/or centrally mediated otologic pathology. These potential underlying otologic disorders should be evaluated by an audiologist and/or otologist.

PATM Overview

The PATM model was developed primarily as the result of a series of clinical studies conducted at the National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (NCRAR). The model is designed to be maximally efficient to have the least impact on clinical resources, while still addressing the needs of all patients who complain about tinnitus. Figure 4, the PATM flowchart [PDF], shows the five levels of progressive tinnitus management. Levels 2–5 are conducted by audiologists. However, it is critical to refer patients to other clinics as appropriate at each level.

Level 1–Triage

Patients report bothersome tinnitus to health care providers in many different clinics. These providers may be unaware of tinnitus management resources that are available to help these patients. The triaging guidelines that we developed (shown in Figure 4) are designed mainly for nonaudiologists who encounter patients complaining of tinnitus. The guidelines reflect accepted clinical practices. A handout that audiologists can share with their health care provider referral sources is found in Tinnitus Triage Guidelines —intended to be provided to nonaudiologist clinicians with patients who complain of bothersome tinnitus.

Some tinnitus patients present with behaviors that indicate the need for an evaluation by a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other licensed mental health professional. Most mental/emotional disorders are not so obvious and may require special evaluations to establish their existence and significance. Many patients with problematic tinnitus and TBI suffer from depression and/or anxiety. Tinnitus patients with these problems should be referred for evaluation by a mental health professional. Patients should also be referred immediately to a mental health professional if they report suicidal ideation, or if they have bizarre thoughts or perceptions such as "hearing voices." Patients with PTSD and severe tinnitus may require test protocol modifications and referrals to mental health that address the powerful limbic system responses.

Level 2–Audiologic Evaluation

Tinnitus is a symptom of dysfunction within the auditory system and usually is associated with some degree of hearing loss. It thus is necessary for tinnitus patients to be evaluated by an audiologist. The evaluation should assess the potential need for medical assessment and/or audiologic intervention (audiologic intervention can address hearing loss, problematic tinnitus, and reduced tolerance to sound). It is sometimes also appropriate to screen for the presence of mental health symptoms and to refer patients to a mental health clinic because these symptoms can interfere with successful self-management of tinnitus.

The Level 2 evaluation includes a standard audiologic evaluation and brief written questionnaires to assess the relative impact of hearing problems and tinnitus problems. When indicated, the Level 2 evaluation can also include a brief structured tinnitus interview and brief written questionnaires to assess appropriateness of referral to a mental health clinic. Tinnitus patients who require amplification are fitted with hearing aids, which often can result in satisfactory tinnitus management with minimal education and support specific to tinnitus. Any patient found to have problematic tinnitus receives "How to Manage Your Tinnitus: A Step-by-Step Workbook" and is invited to attend Level 3–Group Education. The workbook, written at the sixth-grade reading level, contains information on using sound to manage tinnitus, changing thoughts and feelings to manage tinnitus, relaxation techniques, hearing conservation, sleep hygiene tips, and general tinnitus information. Videos of PATM Level 3 counseling and methods of relaxation and imagery based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), as well as a CD demonstrating the different ways that sound can be used to manage tinnitus, are currently under development and will be added to the workbook to provide the audiologist and patient with additional intervention tools in a multimodal format.

Level 3–Group Education

The advantages of a group education format include the following: (a) Education and support can be provided to more patients in less time-maximizing available resources. (b) Patients are empowered to make informed decisions about self-management and further tinnitus intervention options. (c) Patients can support and encourage each other. Recent evidence supports the use of group education as a basic form of tinnitus intervention. Group education has been shown to be effective as part of a hierarchical tinnitus management program at a major tinnitus clinic. The NCRAR completed a randomized clinical trial evaluating group education for tinnitus in almost 300 patients that showed significantly more reduction in tinnitus severity for those in the group education group as compared to control groups.

Level 3-Group Education normally consists of two sessions separated by about 2 weeks. During the first session, the principles of using sound to manage tinnitus are explained, and each participant uses a worksheet that is located in the self-management workbook provided at the Level 2 Audiologic Evaluation to develop an individualized "sound plan" to manage their most bothersome tinnitus situation—see Figure 5, PATM Sound Plan Worksheet [PDF]. Patients are first taught the three types of sound for tinnitus management: "Soothing Sound," used to provide an immediate sense of relief from stress caused by tinnitus; "Background Sound," used to reduce contrast between tinnitus and the acoustic environment (thereby making it easier for the tinnitus to go unnoticed); and "Interesting Sound," used to actively divert attention away from the tinnitus.

For each of the three types of sound for managing tinnitus (soothing, background, and interesting), patients are taught that environmental sound, music, or speech can be applied. Thus, the therapeutic use of sound with PATM can involve all nine combinations of the three types of sound and environmental sound, music, or speech. Patients are instructed to use the sound plan that they developed during the first meeting until the next meeting, at which time they discuss their experiences using the plan and its effectiveness. The audiologist facilitates the discussion and addresses any questions or concerns. Further information about managing tinnitus is then presented, and the participants revise their sound plan based on the discussion and new information. By the end of the second session, the participants should have learned how to develop, implement, evaluate, and revise a sound plan to manage their most bothersome tinnitus situation. They are encouraged to use the Sound Plan Worksheet on an ongoing basis to write additional sound plans for other bothersome tinnitus situations.

Incorporation of CBT Techniques to PATM

Intervention with PATM focuses on assisting patients in learning how to self-manage their tinnitus using therapeutic sound in adaptive ways. Some patients with problematic tinnitus, however, require psychological intervention to alter negative reactions to tinnitus and to aid in coping with tinnitus. This psychological component is particularly important for tinnitus patients who also experience PTSD, depression, anxiety, or other mental health problems. Psychological intervention can be an important component of an overall approach to tinnitus management for patients with mild TBI.

Caution should be used when discussing the use of psychological interventions with patients due to the stigma of mental illness and negative connotations of seeing a psychologist. It should be emphasized that tinnitus is not a psychological condition. Rather, psychologists can assist patients cope with tinnitus using CBT, which is a specific modality of psychotherapy shown to be effective in treating many health conditions.

CBT has been shown to be effective in reducing the annoyance of tinnitus and is an adjunct to the sound-based PATM counseling to address emotional difficulties by teaching patients to learn ways to change their thoughts and feelings about tinnitus. Specifically, patients are taught that relaxation techniques such as deep breathing and imagery can reduce stress and tension caused by tinnitus, and changing how they think about their tinnitus can help them change how they feel about it.

Each participant uses a worksheet to develop an individualized "plan of action" to change their negative thoughts and feelings about tinnitus-see Figure 6, PATM Changing Thoughts and Feelings Worksheet [PDF]. Patients are first taught the following: "Deep Breathing," to reduce stress caused by tinnitus by helping the patient relax; "Imagery," to reduce stress caused by tinnitus by helping the patient relax and diverting attention off of the tinnitus; and "Changing Thoughts," to change how the patient thinks about his or her tinnitus to help change the ways he or she feels about it. Patients are then able to choose from these three options to learn what works best in different situations.

It should be noted that when providing PATM to patients with TBI, it may be advised to use the Level 5 individualized counseling flip chart for one-on-one education at Level 3 versus the group education class format.

Level 4–Tinnitus Evaluation

Most patients can satisfactorily self-manage their tinnitus after participating in Level 3–Group Education. Patients who need more support and education than are available at Level 3 can progress to the PATM Level 4–Tinnitus Evaluation to determine their needs for further intervention. The Level 4–Tinnitus Evaluation includes an intake interview and a tinnitus psychoacoustic assessment. Administration of the intake interview is the primary means of determining whether one-on-one individualized tinnitus management is needed. If so, then the audiologist and patient begin to formulate a management plan. Special procedures are used to select devices for tinnitus management, including ear-level noise generators and combination instruments, and personal listening devices. Screening for referral to mental health is required at the Level 4–Tinnitus Evaluation; however, mental health screening should always be considered at any level of management if patients' comments and discourse point to significant mental health issues.

Following completion of the Level 4–Tinnitus Evaluation, patients must meet certain criteria to be considered for Level 5–Individualized Management, namely (a) Levels 1–4 of PATM have not met their needs, and (b) they have been evaluated and referred to other health care providers as warranted.

Level 5–Individualized Management

Individualized management is needed by relatively few patients. Level 5–Individualized Management uses a standardized, individualized counseling flip chart to provide directed counseling as well as discussion of sound management and relaxation strategies. If individualized management is not effective after about 6 months, then different forms of tinnitus intervention such as neuromonics tinnitus treatment, tinnitus masking, tinnitus retraining therapy, and tinnitus focused CBT should be considered.

Clinical Management for Veterans With Tinnitus Associated With TBI

Blast-related TBI is a major problem among returning veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. A large percentage of these patients also are reporting tinnitus in VA clinics. Tinnitus can occur not only as a direct consequence of the injury causing TBI but also as a side effect of medications commonly used to treat cognitive, emotional, and pain problems associated with TBI. Tinnitus usually is a lifelong condition that can significantly affect quality of life. It is important for audiologists to determine all the factors that may have a negative impact on the communication function of persons with TBI. Because the population with TBI can vary greatly in terms of tinnitus severity, peripheral and central function, speech perception abilities in quiet and degraded conditions, cognition, and emotional, behavioral, and physical health, there is no universal standardized approach to audiologic management or tinnitus management of persons with TBI.

Audiologists should evaluate and counsel patients according to their needs. Some patients with mild TBI require more evaluation and management than others, particularly when dealing with patients with overlapping PTSD and/or mental conditions, problematic tinnitus, central auditory processing disorder, and/or vestibular complaints. The family is one of the most important factors in a patient's recovery. The audiologist should support the patient and family and provide education and training for real-world success in self-management. Rehabilitation and education are crucial elements in treating TBI. When counseling patients with TBI, it is important to provide a calm and structured environment with minimal auditory and visual distractions, reduce the complexity and talk about one topic, repeat key points, speak slowly, pause, use tag words (e.g., first, last, before, and after), provide supplemental written information, and finally to ask the patient to "teach back" the information you provided to assess learning and reteach as indicated.

No program currently exists to provide clinical management for military personnel and veterans who have tinnitus associated with TBI. A pilot study funded by VA RR&D using a national, centralized tinnitus management counseling program via telephone that is thus accessible to individuals from any geographic location is currently being formally evaluated. The program is based on the educational counseling methods of PATM with modifications to include individualized brief telephone interventions with an audiologist and a psychologist; also, patients receive via mail a supplemental self-management workbook and DVD consisting of use of therapeutic sound, relaxation techniques to include deep breathing, guided imagery, sleep hygiene tips, and changing thoughts and feelings.

Conclusion

The PATM model is designed for implementation at any audiology clinic that desires to optimize resourcefulness, cost efficiency, and expedience in its practice of tinnitus management. Also, PATM has been adapted to quickly identify and meet the unique tinnitus management needs of veterans and military members with TBI. This modified centralized approach to tinnitus management allows for frequent and brief intervention to accommodate the needs of people with impaired memory, limited concentration, and other cognitive difficulties often associated with TBI. While a brief overview, this article provides the essential elements of PATM and the problematic overlap of mental health factors and TBI. Those wishing further details are referred to the resources below that provide the basis behind the information presented herein and are the suggested readings for continued study in this area.

About the Authors

Dr. Paula Myers is Chief of the Audiology Section and Cochlear Implant Coordinator at the James A. Haley VA Medical Center/Polytrauma Rehabilitation Center in Tampa, Florida, and has been employed there for 22 years. Her research focuses on the development of patient health education programs and materials, standardized protocols for clinical assessment and management of tinnitus, and blast injury and auditory dysfunction. She has received funding from the VA Rehabilitation Research and Development Service to conduct research as a Co-Principal Investigator on studies related to tinnitus management and traumatic brain injury. Contact her at paula.myers@va.gov.

James Henry, PhD, has been working at the VA at the National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research (NCRAR) in Portland, Oregon, for the past 22 years and has conducted tinnitus research for 16 years. His research focuses on developing standardized protocols for clinical assessment and management of tinnitus, and conducting randomized clinical trials to assess outcomes of different methods of tinnitus intervention. Contact him at james.henry@va.gov.

Tara L. Zaugg, AuD, is a licensed, certified, and clinically privileged research audiologist employed at the NCRAR, in Portland, Oregon. Through her involvement in tinnitus clinical trials over the last 8 years at the NCRAR, she has developed considerable expertise in tinnitus assessment and management, and in the training of audiologists to perform tinnitus management. Contact her at tara.zaugg@va.gov.

Caroline J. Kendall, PhD, is a research psychologist at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, and associate research scientist at Yale University. Her research interest focuses on the psychological interventions for tinnitus and the comorbidities of mental health disorders with tinnitus. Contact her at caroline.kendall@va.gov.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Axelsson, A., & Barrenas, M. L. (1992). Tinnitus in noise-induced hearing loss. In A. L. Dancer, D. Henderson, R. J. Salvi, & R. P. Hamnernik (Eds.), Noise-induced hearing loss (pp. 269–276). St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book.

Bryant, R. A. (2008). Disentangling mild traumatic brain injury and stress reactions. New England Journal of Medicine, 358, 525–527.

Cave, K. M., Cornish, E. M., & Chandler, D. W. (2007). Blast injury of the ear: Clinical update from the global war on terror. Military Medicine, 172, 726–730.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2003). Report to Congress on mild traumatic brain injury in the United States: Steps to prevent a serious public health problem. Atlanta, GA: Author.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2006). Report to Congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Author.

Chandler, D. (2006, July 11). Blast-related ear injury in current U.S. military operations. The ASHA Leader, 11(9), pp. 8–9, 29.

Cicerone, K. D., & Kalmar, K. (1995). Persistent post-concussive syndrome: Structure of subjective complaints after mild traumatic brain injury, Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 10(3), 1–17.

Cohen, J. T., Ziv, G., Bloom, J., Zikk, D., Rapoport, Y., & Himmelfarb, M. Z. (2003). Blast injury of the ear in a confined space explosion: Auditory and vestibular evaluation. Israeli Medical Association Journal, 4, 559–562.

DePalma, R. G., Burris, D. G., Champion, H. R., & Hodgson, M. J. (2005). Blast injuries. New England Journal of Medicine, 352, 1335–1342.

Dobie, R. A. (2004). Overview: Suffering from tinnitus. In J. B. Snow (Ed.), Tinnitus: Theory and management (pp. 1–7). Lewiston, NY: Decker.

Fagelson, M. A. (2007). The association between tinnitus and posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Audiology, 16(2), 107–117.

Gondusky, J. S., & Reiter, M. P. (2005). Protecting military convoys in Iraq: An examination of battle injuries sustained by a mechanized battalion during Operation Iraqi Freedom II. Military Medicine, 170, 546–549.

Helling, E. R. (2004). Otologic blast injuries due to the Kenya embassy bombing. Military Medicine, 169, 872–876.

Henry, J. A., Schechter, M. A., Zaugg, T. L., Griest, S. E., Jastreboff, P. J., Vernon, J. A.,et al. (2006). Outcomes of clinical trial: Tinnitus masking versus tinnitus retraining therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 17, 104–132.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L, Myers, P. J., & Kendall C. J. (2009). How to manage your tinnitus: A step-by-step workbook (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L., Myers, P. J., Kendall, C. J., & Turbin, M. B. (2009). Principles and application of educational counseling used in progressive audiologic tinnitus management. Noise and Health, 11(42), 33–48.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L., Myers, P. J., & Schechter, M. A. (2008a, June 17). Progressive audiologic tinnitus management. The ASHA Leader, 13(8), pp. 14–17.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L., Myers, P. J., & Schechter, M. A. (2008b). The role of audiologic evaluation in progressive audiologic tinnitus management. Trends in Amplification, 12(3), 170–187.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L., Myers, P. J., & Schechter, M. A. (2008c). Using therapeutic sound with progressive audiologic tinnitus management. Trends in Amplification, 12(3), 188–209.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L., & Schechter, M. A. (2005a). Clinical guide for audiologic tinnitus management I: Assessment. American Journal of Audiology, 14, 21–48.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L., & Schechter, M. A. (2005b). Clinical guide for audiologic tinnitus management II: Treatment. American Journal of Audiology, 14, 49–70.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L., Schechter, M. A., & Myers, P. J. (2008). How to manage your tinnitus: A step-by-step workbook (1st ed.). Portland, OR: National Center for Rehabilitative Auditory Research.

Henry, J. L., & Wilson, P. H. (2001). The psychological management of chronic tinnitus . Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Hoge, C. W., McGurk, D., Thomas, J. L., Cox, A. L., Engel, C. C., & Castro, C. A. (2008). Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq. New England Journal of Medicine, 358, 453–563.

Kay, T., Harrington, D. E., Adams, R., Anderson, T., Berral, S., Cicerone, K., et al. (1993). Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 8(3), 86–87.

Kennedy, J. E., Jaffee, M. S., Leskin, G. A, Stokes, J. W., Leal. F. O., & Fitzpatrick, P. J. (2007). Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic disorder-like symptoms and mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 44, 895–920.

Lew, H. L., Guillory, S. B., Jerger, J., & Henry, J. A. (2007). Auditory dysfunction in traumatic brain injury. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 44, 929–936.

Lux, W. E. (2007). A neuropsychiatric perspective on traumatic brain injury. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 44, 951–962.

McMillan, T. M. (2001). Errors in diagnosing post-traumatic stress disorder after traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 15(1), 39–46.

Mrena, R., Savolainen, S., Kuokkanen, J. T., & Ylikoski, J. (2002). Characteristics of tinnitus induced by acute acoustic trauma: A long-term follow up. Audiology and Neuro-otolology, 7, 122–130.

Myers, P. J., Henry, J. A., & Zaugg, T. L. (2008). Considerations for persons with mild traumatic brain injury. Perspectives on Audiology, 4(1), 21–34.

Myers, P. J., Wilmington, D. J., Gallun, F. J, Henry, J. A., & Fausti, S. A. (2009). Hearing impairment and traumatic brain injury among soldiers: Special considerations for the audiologist. Seminars in Hearing, 30(1), 5–27.

Okie, S. (2006). Reconstructing lives-a tale of two soldiers. New England Journal of Medicine, 355, 2609–2615.

Taber, K. H., Warden, D. L., & Hurley, R. A. (2006). Blast-related traumatic brain injury: What is known? Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 18, 141–145.

Veterans Health Administration. (2007). VHA Directive 2007-013: Screening and evaluation of possible traumatic brain injury in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) veterans. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

Resources

- For more details about the diagnosis and treatment of TBI, see Veterans Health Initiative, Traumatic Brain Injury: A CME Program [PDF].

ASHA Policy Documents

- Preferred Practice Patterns for the Profession of Audiology (2006)

- Scope of Practice in Audiology (2018)

- Guidelines for Manual Pure-Tone Threshold Audiometry (2005)

- Evidence-Based Practice in Communication Disorders: An Introduction – Technical Report (2004)

- Knowledge and Skills Required for the Practice of Audiologic/Aural Rehabilitation (2001)

- External Auditory Canal Examination and Cerumen Management – Guidelines, Knowledge and Skills, Position Statement (1992)

Additional References

Ahmad, N., & Seidman, M. (2004). Tinnitus in the older adult: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment options. Drugs & Aging, 21(5), 297–305. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Andersson, G. (2001). The role of psychology in managing tinnitus: A cognitive behavioral approach. Seminars in Hearing, 22(1), 65. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Andersson, G., Ingerholt, C., & Jansson, M. (2003). Autobiographical memory in patients with tinnitus. Psychology & Health, 18(5), 667–675. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Bartnik, G., Fabijanska, A., & Rogowski, M. (2001). Experiences in the treatment of patients with tinnitus and/or hyperacusis using the habituation method. Proceeding of the 4th European Conference in Audiology, Oulu, Finland, June 6–10, 1999. Scandinavian Audiology. Supplementum, 30, 187–190. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Davis, P.B., Paki, B., & Hanley, P. J. (2007). Neuromonics tinnitus treatment: Third clinical trial. Ear and Hearing, 28(2), 242–259.

Gold, S., Formby, C., & Gray, W. (2000). Celebrating a decade of evaluation and treatment: The University of Maryland Tinnitus & Hyperacusis Center. American Journal of Audiology, 9(2), 69–74. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Hall, J., & Haynes, D. (2001). Audiologic assessment and consultation of the tinnitus patient. Seminars in Hearing, 22(1), 37. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Handscomb, L. (2006). Analysis of Responses to Individual Items on the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory According to Severity of Tinnitus Handicap. American Journal of Audiology, 15, 102–107.

Henry, J.A. (2004). Audiologic assessment. In J. B. Snow (Ed.), Tinnitus: Theory and management, (pp. 220–236). Lewiston, NY: Decker.

Henry, J., Dennis, K., & Schechter, M. (2005). General review of tinnitus: Prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48(5), 1204–1235. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Henry, J., Jastreboff, M., Jastreboff, P., Schechter, M., & Fausti, S. (2002). Assessment of patients for treatment with tinnitus retraining therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 13(10), 523–544. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Henry, J., Loovis, C., Montero, M., Kaelin, C., Anselmi, K., Coombs, R., et al. (2007). Randomized clinical trial: Group counseling based on tinnitus retraining therapy. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 44(1), 21–31. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Henry, J., Schechter, M., Nagler, S., & Fausti, S. (2002). Comparison of tinnitus masking and tinnitus retraining therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 13(10), 559–581. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Herraiz, C., Diges, I., Cobo, P., Plaza, G., & Aparicio, J. (2006). Auditory discrimination therapy (ADT) for tinnitus managment [sic]: Preliminary results. VIIIth International Tinnitus Seminar. Held in Pau, France, 6–10 September, 2005. Acta Oto-Laryngologica (Supplement), 126, 80–83. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Hilton, M., & Stuart, E. (2004). Ginkgo biloba for tinnitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Holgers, K., Zager, S., & Svedlund, K. (2005). Predictive factors for development of severe tinnitus suffering-further characterisation. International Journal of Audiology, 44(10), 584–592. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Jastreboff, P. J., & Hazell, J. W. P. (2004). Tinnitus retraining therapy: Implementing theneurophysiological model. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kentish, R., Crocker, S., & McKenna, L. (2000). Children's experience of tinnitus: A preliminary survey of children presenting to a psychology department. British Journal of Audiology, 34(6), 335–340. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Martinez Devesa, P., Waddell, A., Perera, R., & Theodoulou, M. (2007). Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

McFerran, D., & Baguley, D. (2008). The efficacy of treatments for depression used in the management of tinnitus. Audiological Medicine, 6(1), 40–47. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

McKenna, L. (2004). Models of tinnitus suffering and treatment compared and contrasted. Audiological Medicine, 2(1), 41–53. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Meikle, M.B., Creedon, T.A, & Griest, S.E. (2004). Tinnitus archive (2nd ed.). Retrieved May 9, 2008, from http://www.tinnitusarchive.org/.

Newman, C.W., Jacobson, G.P., & Spitzer, J.B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 122, 143–148.

Newman, C.W., & Sandridge, S.A. (2005). Incorporating group and individual sessions into a tinnitus management clinic. In R. S. Tyler (Ed.), Tinnitus treatment: Clinical protocols (pp. 187–197. New York: Thieme.

Newman, C.W., Sandridge, S.A., & Jacobson, G.P. (1998). Psychometric adequacy of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) for evaluating treatment outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 9, 153–160.

Newman, C., Sandridge, S., Meit, S., & Cherian, N. (2008). Strategies for managing patients with tinnitus: A clinical pathway model. Seminars in Hearing, 29(3), 300–309. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Reich, G. (2001). The role of informal support and counseling in the management of tinnitus. Seminars in Hearing, 22(1), 7. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Roy, D., & Chopra, R. (2002). Tinnitus: An update. Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 122(1), 21–23. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Sandridge, S.A., & Newman, C.W. (2005). Benefits of group informational counseling. In R. Dauman (Ed.), VIIIth International Tinnitus Seminar (p. 106). Bordeaux, France: University Hospital of Bordeaux, ENT Department.

Sindhusake, D., Golding, M., Wigney, D., Newall, P., Jakobsen, K., & Mitchell, P. (2004). Factors predicting severity of tinnitus: A population-based assessment. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 15(4), 269–280. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Tonkin, J. (2002). Tinnitus: More can be done than most GPs think. Australian Family Physician, 31(8), 712. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

Tyler, R., Haskell, G., Gogel, S., & Gehringer, A. (2008). Establishing a tinnitus clinic in your practice. American Journal of Audiology, 17(1), 25–37. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from CINAHL Plus with Full Text database.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. (2005). Screening for PTSD in a primary care setting. [Fact sheet]. Retrieved June 13, 2008 from http://www.ncptsd.va.gov/ncmain/ncdocs/fact_shts/fs_screen_disaster.html.

Vernon, J.A., & Meikle, M.B. (2000). Tinnitus masking. In R.S. Tyler (Ed.), Tinnitus handbook (pp. 313–356). San Diego,CA: Singular.

White, S.C. (2009, March 3). Tinnitus evaluation and intervention. The ASHA Leader, 14(3), 3–4.

Websites

The following websites and other resources are provided for the convenience of our readers. ASHA does not endorse specific programs, products, or services.